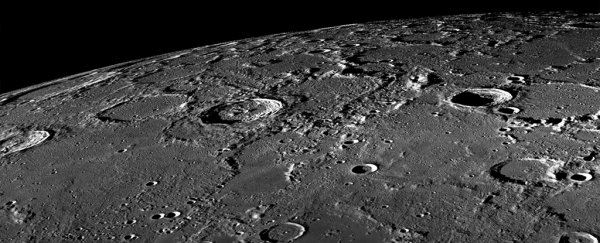

Small pits in a large crater on the Moon's North Pole could be "skylights" leading down to an underground network of lava tubes – tubes holding hidden water on Earth's nearest neighbour, according to new research.

There's no lava in them now of course, though that's originally how the tubes formed in the Moon's fiery past. But they could indicate easy access to a water source if we ever decide to develop a Moon base sometime in the future.

Despite the Moon's dry and dusty appearance, scientists think it contains a lot of water trapped as frozen ice. What these new observations carried out by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) show is that it might be much more accessible than we thought.

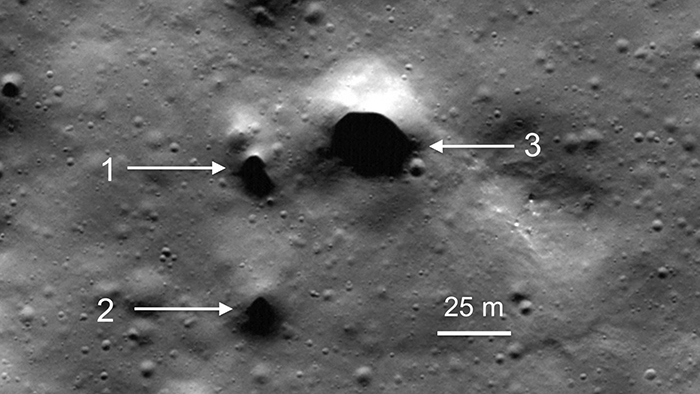

The potential skylights. (SETI Institute)

The potential skylights. (SETI Institute)

"The highest resolution images available for Philolaus Crater do not allow the pits to be identified as lava tube skylights with 100 percent certainty, but we are looking at good candidates considering simultaneously their size, shape, lighting conditions, and geologic setting," says the researcher behind the study, planetary scientist Pascal Lee from the SETI Institute.

The crater in question is about 70 kilometres (43 miles) across, and if you want to dig your Moon maps out, the new pits were spotted at 72.1°N, 32.4°W, about 550 kilometres (340 miles) from the Moon's North Pole, on the side of the Moon facing Earth.

The pits themselves are 15-30 metres (up to 98 feet) across and are thought to be a way in to the collapsed lava tubes – or sinuous rilles – criss-crossing the crater. These aren't the first pits to be spotted, but crucially, they're the first to be seen in the Moon's polar regions, close to where the ice may be buried.

Scientists have long been thinking about how to extract the ice reserves we think are up there – solar power was originally out of the question, as it's the freezing shadowed areas of the Moon that have preserved the ice in the first place.

Not only would natural skylights like these provide easier access to the underground ice, it would also mean solar power would be back on the table as an idea. Otherwise, we're going to be faced with a long and laborious job of extracting water from the Moon's soil.

What exploring a crater – on Mars or the Moon – could look like. (SETI Institute)

What exploring a crater – on Mars or the Moon – could look like. (SETI Institute)

What's more, due to the Philolaus Crater's relative youth – having formed within the last 1.1 billion years or so – it could give lunar explorers in the region some extra insight into how the Moon became the way it is today.

As an added bonus, ice excavators – whether human or robot – would have a very picturesque view of our planet while they worked.

"The Apollo landing sites were all near the Moon's equator, such that the Earth was almost directly overhead for the astronauts," says Lee. "But from the Philolaus skylights, Earth would loom just over the crater's mountainous rim, near the horizon to the southeast."

There are still a lot of ifs and buts here – more studies are needed to establish whether these are indeed access points for lava tubes, even before we get to the question of whether scientists are right about the ice reserves – but it's a promising finding.

And with renewed talk of a new manned mission to the Moon, this site would be a good bet for a visit and perhaps a long-term lunar base. That would give us some useful practice for further planetary explorations too.

"Exploring lava tubes on the Moon will also prepare us for the exploration of lava tubes on Mars," says Lee. "There, we will face the prospect of expanding our search for life into the deeper underground of Mars where we might find environments that are warmer, wetter, and more sheltered than at the surface."

The findings have been presented at NASA's Lunar Science for Landed Missions Workshop at the Ames Research Center in California.