Scientists thought that the spleen is where malaria parasites go to die.

Now, a team of researchers has discovered "a surprisingly large" amount of live Plasmodium parasites hiding out in the spleens of people with chronic malaria infections.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the multistep life cycle of mosquito-borne malaria parasites, some of which can lay dormant in the liver before bursting out into the bloodstream to multiply and spread.

It also helps to explain why chronic cases of malaria fly under the radar on blood tests but then suddenly relapse, and also how some malaria parasites have adapted to survive.

"Our findings redefine the malaria life-cycle," says Steven Kho, an infectious disease researcher at the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, Australia.

"Chronic malaria should be considered predominantly an infection of the spleen, with just a small proportion circulating in the blood."

In two papers, Kho and his colleagues report discovering two of the five species of Plasmodium parasites known to cause malaria in humans – P. falciparum and P. vivax – lurking in the spleens of people living in Papua, Indonesia, where malaria is endemic and chronic cases are common.

Although P. falciparum is the deadliest form of malaria parasite, P. vivax poses a greater challenge to disease eradication; the latter is spread more widely across the globe and causes recurring infections, effectively hiding without easy detection in-between bouts.

Cases of chronic P. vivax malaria, which can still be fatal, are also on the rise as disease control activities hone in on P. falciparum, a sign of how this horrid disease keeps thwarting our best efforts.

"The recent drive to rid the world of malaria has brought P. vivax to the fore," explains parasitologist Georges Snounou in a different paper from 2018, "with the recognition that relapses pose a serious obstacle to its eradication."

Of the new work, the first study - led by Kho - describes a group of 15 adults who showed no symptoms of malaria and had their spleens surgically removed for other medical reasons.

Using microscopes and cell staining to expose the parasites in blood samples and spleen tissue, the researchers found most of these people had bulk Plasmodium parasites in their spleen.

In an extension of this first study, expanding the total number of volunteers out to 22, the researchers again identified significant numbers of parasites in spleens, in spite of patients presenting no symptoms of malaria.

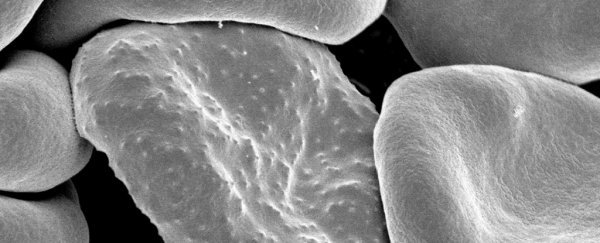

Red cells infected with P. vivax in the spleen. (Kho et al. 2021)

Red cells infected with P. vivax in the spleen. (Kho et al. 2021)

The spleen has the job of filtering our blood to remove old, damaged, or infected red blood cells. The levels of P. vivax that had accumulated in these people's spleens were in some cases hundreds, even thousands of times higher than what was found circulating in the bloodstream.

This was way more than you'd expect to see if the parasites were only replicating in red blood cells that the spleen strained out of circulation, the researchers calculated.

So, the findings suggest that the spleen is a previously unrecognized reservoir where Plasmodium parasites can hang out and replicate.

"Accumulation of parasites in the spleen was found with both major Plasmodium species causing malaria, but was particularly apparent in P. vivax, where over 98 percent of all the parasites in the body were hiding in the spleen," Kho explains.

What's more, a couple of people had such low levels of malaria parasites in their blood it was undetectable, yet their spleens were packed full of parasite-infected cells. This has researchers worried, but with so few examples to date, larger studies are really needed to further validate the findings.

"This is another factor limiting the success of malaria elimination programs relying on mass testing of blood and only treating those with detectable infection," says infectious disease physician Nick Anstey, noting how this could hamper surveillance and eradication efforts.

But why P. vivax accumulates so intensely in the spleen, well – that's still an unknown. The researchers have a hunch though: the spleen stockpiles a lot of young red blood cells called reticulocytes, which are the only type of red cells that P. vivax can infect.

"This makes the spleen a highly favorable location in which the vivax malaria parasites can multiply," Anstey says.

This may also reinvigorate research into malaria treatments and vaccine candidates that attack different stages of the Plasmodium life cycle, now that we know the spleen is a crucial part of the puzzle for P. vivax infections.

Both are sorely needed for this disease which infects around 250 million people each year in the Asia-Pacific region alone, and for P. vivax which has been long overlooked in research.

The studies were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and PLOS Medicine.