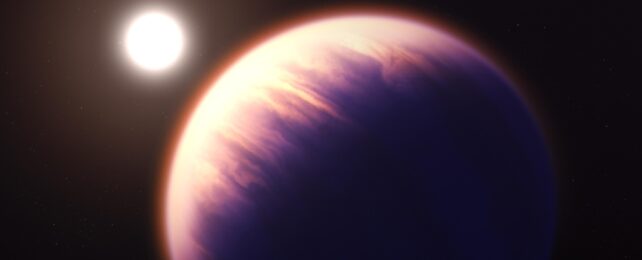

The galaxy can throw some odd curveballs, but an exoplanet discovered 1,232 light-years away is one of the oddest yet.

It's WASP-193b, and while it's nearly 50 percent bigger than Jupiter, it's so light and fluffy that its overall density is comparable to that of cotton candy. It's just a hair over 1 percent of the density of Earth. It's an absolute dandelion puff-ball of a world… if a dandelion puff-ball could be a planet.

While not unheard of, exoplanets like WASP-193b are rare, and they could help us better understand planetary evolution, according to an international team led by astronomer Khalid Barkaoui of the University of Liège in Belgium.

"WASP-193b is the second least dense planet discovered to date, after Kepler-51d, which is much smaller," Barkaoui explains.

"Its extremely low density makes it a real anomaly among the more than five thousand exoplanets discovered to date. This extremely low density cannot be reproduced by standard models of irradiated gas giants, even under the unrealistic assumption of a coreless structure."

Looking at all the weird and wonderful worlds that are out there not only allows us to contextualize our Solar System but offers a window into how planetary systems form and evolve.

Gas giants close to their stars are an excellent tool for this because our understanding of planetary formation means that they had to have formed elsewhere and migrated inwards. In addition, irradiation from the star also means that many of these worlds are shrinking.

WASP-193b is an exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star named WASP-193. This star is around 1.1 times the mass and 1.2 times the radius of the Sun and is very close to the Sun in temperature and age. But WASP-193b orbits its star way more closely than any of the Solar System's planets: It zooms around once every 6.25 days.

Studying how the star's light changes as the exoplanet whips around it allowed Barkaoui and his colleagues to calculate the world's radius and mass. Its radius is around 1.46 times the radius of Jupiter. But its mass is incredibly small by comparison: just 0.139 times Jupiter's.

From these properties, the researchers derived the exoplanet's density: 0.059 grams per cubic centimeter. By comparison, Earth has a density of 5.51 grams per cubic centimeter. Jupiter's density is 1.33 grams per cubic centimeter, which makes sense – it has a lot of clouds going on. Cotton candy has a density of 0.05 grams per cubic centimeter.

"The planet is so light that it's difficult to think of an analogous, solid-state material," says planetary scientist Julien de Wit from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"The reason why it's close to cotton candy is because both are pretty much air. The planet is basically super fluffy."

Very few other worlds have been found with comparable density, but they offer some clues as to how such fluffy worlds can come to exist. Close proximity to a star can heat the atmosphere, puffing it out, especially if that atmosphere was predominantly hydrogen and helium.

But such a world would only look like WASP-193b for a few tens of millions of years or so, when the star is younger and hotter; in addition, the heat and winds from the star could strip such a tenuous atmosphere pretty quickly.

So this poses some problems. The star is thought to be up to 6 billion years old; while there could be some mechanism for internal heat puffing up WASP-193b's atmosphere, the observed properties of the exoplanet cannot be recreated using sophisticated planetary evolution models.

"WASP-193b is a cosmic mystery. Solving it will require some more observational and theoretical work," says Barkaoui.

The good news is that WASP-193b represents an excellent candidate for follow-up studies to see what its atmosphere is made of. This is one of the tasks the James Webb Space Telescope was designed for; just one transit observation, the team says, could yield insights that explain how such a strange, fluffy, old world can exist in the Universe.

A version of this article was first published in July 2023 and has been rerun as the team's paper has now been published in Nature Astronomy.