Digging deep into the Volyn quartz mine, near the city of Zhytomyr in Ukraine, scientists have discovered the oldest three-dimensional microfossils ever found – trapped in time some 1.5 billion years ago.

Being able to get a window that far back into history is of course hugely exciting for experts. Fossils can tell us a lot about Earth's past, but the further back in time you go, the less solid physical evidence we have.

A team from the Technical University of Berlin (TU Berlin) and the Museum of Natural History Berlin in Germany, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and National Museum of Natural History in Luxembourg, used a technique known as scanning electron microscopy to spot the fossils in an ultra-thin layer of aluminum silicate.

"We were actually looking to study beryl and topaz from the mine," says geoscientist Gerhard Franz, from TU Berlin. "What we have found now is far more valuable than any gemstones."

A very particular set of geological circumstances preserved these microfossils. These life-forms would most likely have survived on minerals deep underground, and the researchers suggest subterranean geysers of hydrofluoric acid, created by water and heat, would've produced the aluminum and silicon required to coat and preserve the creatures.

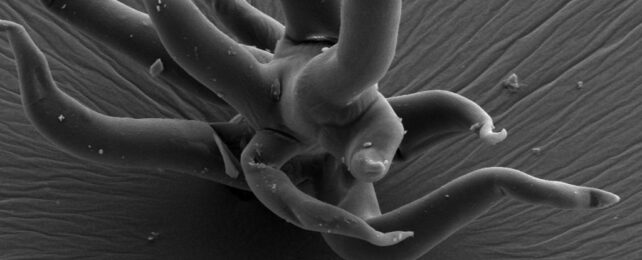

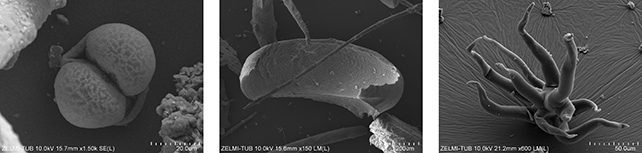

The thickness of the microorganisms varies between around 10 micrometers – a tiny fraction of a millimeter – and several millimeters, and they're structured like microscopic filaments, shells, and fungi.

The shapes and the associated minerals detected suggest some of the mysterious life forms are multicellular fungi-like organisms. Others had shell-like sheaths around their cells. Some of these structures haven't been seen before, making the discovery even more interesting.

"What we are looking at now under our electron microscope are mostly fibrous structures," says Franz. "Either thin filaments that branch out, or thick ones that have small protrusions or dents."

Scientists know very little about life before the Cambrian explosion, around 540 million years ago – not least because it wasn't until that sudden burst of life that organisms developed the shells and skeletons that could be preserved as fossils.

The Precambrian period that these fossils date from is known as 'the boring billion', with billion referring to the number of years. With no skeletons to preserve, scientists have had to look at the faintest traces of evidence of life for clues to our distant past.

Now, they've got some solid clues – in 3D – of the kind of life that existed billions of years ago. That's not only useful in studying Earth's history, it could also give us clues about how life might develop on other planets.

"Further investigations and possibly new finds will be able to tell us even more about the primordial microorganisms, especially about previously unknown forms on the continents, and not just in the sea," says Franz.

The research has been published in the journal Biogeosciences, here and here.