Titan is a mystery as mighty as its namesake. A thick haze of atmospheric nitrogen conceals the moon's surface from view, hiding a giant and ancient geological oddity that scientists have only just unmasked.

In new research, scientists report the discovery of a massive 'corridor' of ice-rich bedrock that spans almost halfway around Saturn's largest satellite, stretching for an epic 6,300 kilometres (3,900 miles) in total – a length equivalent to 40 percent of Titan's overall circumference.

"This icy corridor is puzzling, because it doesn't correlate with any surface features nor measurements of the subsurface," says planetary scientist Caitlin Griffith from the University of Arizona.

Griffith and her team pored through thousands of spectral images taken by the Cassini space probe, using an infrared spectrometer instrument to peer as far as possible through Titan's opaque haze.

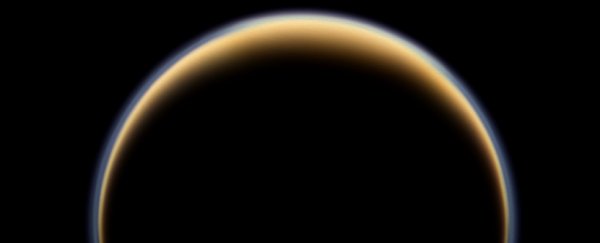

The ice corridor, mapped in blue. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

The ice corridor, mapped in blue. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

With a technique called principal component analysis (PCA) to tease out and refine surface features obscured in the data, the team identified the giant ice oddity straddling Titan's equator.

"Our PCA study indicates that water ice is unevenly, but not randomly, exposed across Titan's tropical surface," the authors write in their paper.

"Most of the exposed ice-rich material follows a long, nearly linear, corridor that stretches 6,300 km from roughly (30° E, 15° N) to (110° W, 15° S)."

What's most unusual about this feature is that it exists at all, since Titan's surface is thought to be largely covered in organic sediment that rains down from the breakup of methane molecules in the atmosphere due to sunlight.

Amidst this strange, wet, and gassy environment, which Griffith characterises as a "deranged version of Earth", it's not exactly clear how the exposed ice structure fits in, so the team thinks it could be a relic of another age, frozen in time.

"It's possible that we are seeing something that's a vestige of a time when Titan was quite different," Griffith told New Scientist.

"It can't be explained by what we see there now."

According to the researchers, the most likely cause could be the legacy of ancient cryovolcanism: 'ice volcanoes' that produce water, ammonia, or methane, in place of the rocky magma we know on Earth.

But since Titan wasn't currently thought to have any active ice volcanoes, it remains a bit of a mystery as to why this giant ice corridor still stands – although that state of affairs might not last much longer, depending on how hard the moon's methane rain continues to fall.

"We detect this feature on steep slopes, but not on all slopes," says Griffith.

"This suggests that the icy corridor is currently eroding, potentially unveiling presence of ice and organic strata."

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy.