It's not every day that an asteroid from outside the Solar System comes whizzing past your front door. In fact, it's only ever happened once that we've observed, when astronomers spotted interstellar asteroid 'Oumuamua in October.

Now a collective of astronomers and engineers wants to seize the opportunity to study 'Oumuamua - by chasing after it with a rocket. They've named the initiative Project Lyra.

It's a bit of a crazy idea, but 'Oumuamua could be utterly worth it. Even with its interstellar origin notwithstanding, it's unlike any asteroid humans have observed before.

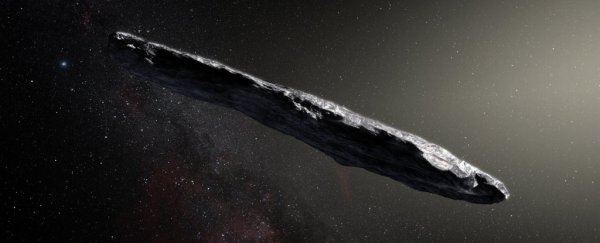

The cigar-shaped asteroid is up to 10 times longer than it is wide, a shape never before seen in an asteroid in the Solar System. It's rocky, and possibly rich in metals, and reddened by cosmic irradiation.

It came from the direction of the star Vega in the Lyra constellation, at a breakneck speed of 95,000 kilometres per hour (59,000 miles per hour).

At first it was thought to have come from Vega's orbit - but it would have taken 300,000 years to get here at that speed. As of 300,000 years ago, Vega was in a different position in the sky.

This means 'Oumuamua could have missed Vega altogether, and been travelling through space, all alone, for hundreds of millions of years.

Researching it could tell us more about the solar system in which it formed, as well as something about extrasolar asteroids, which may be entering our Solar System more frequently than we thought.

This is why a volunteer collective of scientists and engineers called the Initiative for Interstellar Studies wants to send a rocket to check it out. But it would be a lot more complicated than landing a probe on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko - and that was a very complicated business.

By far the biggest obstacle to getting to 'Oumuamua is catching up to it. Comet 67P orbits the Sun, so it's not going anywhere - but 'Oumuamua is already racing on its way out of our Solar System at blistering speed.

As it slingshotted past the Sun, it picked up velocity, and as of 20 November, its speed was 138,000 kilometres per hour (85,700 miles per hour, or 38.3 kilometres per second). It's expected to pass Jupiter's orbit in May 2018.

It took Rosetta 10 years to reach Comet 67P 510 million kilometres (317 million miles) from Earth. It took NASA probe Juno 5 years to reach Jupiter's orbit, 588 million kilometres (365 million miles) away.

Even Pluto probe New Horizons, which broke the record for launch velocity from Earth, and Voyager I, the fastest human-made object to leave the Solar System, are both less than half as fast as 'Oumuamua's current speed.

New Horizons launched at an incredible 58,536 kilometres per hour (36,373 miles per hour), and Voyager I's velocity is 61,200 kilometres per hour (38,000 miles per hour).

But this technical challenge, the Initiative says, is worthwhile in and of itself.

"Besides the scientific interest of getting data back from the object, the challenge to reach the object could stretch the current technological envelope of space exploration," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Hence, Project Lyra is not only interesting from a scientific point of view but also in terms of the technological challenge it presents."

Amongst key elements are travel time, spacecraft velocity, characteristic energy, and the velocity of the asteroid. The researchers have modelled, with launch dates between 5 and 30 years from now, how much velocity such a probe would need to attain in order to catch up to 'Oumuamua.

There's one key problem, though: the calculations were based on 'Oumuamua's incoming speed of 95,000 kilometres per hour. It will gradually return to that speed, but not for a few years.

Perhaps with propulsion technologies currently under development, such as solar sails, higher spacecraft speeds may become possible within a timeframe that would allow a probe to catch the speeding asteroid.

In the meantime, though, we can always improve detection systems so that we can try and catch the next one.

"An important result of our analysis is that the value of a laser beaming infrastructure from the Breakthrough Initiatives' Project Starshot would be the flexibility to react quickly to future unexpected events, such as sending a swarm of probes to the next object like 1I/'Oumuamua," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"With such an infrastructure in place today, intercept missions could have reached 1I/'Oumuamua within a year."

You can read the paper in full from the pre-print resource arXiv.