Mammals are some of the most well-researched animals on Earth, yet there are potentially hundreds of undescribed species still hiding in the wild, according to new predictive modeling.

Machine learning suggests most of these unknown creatures are small-bodied, like bats, rodents, and shrews. Their size has probably made it difficult for experts to identify morphological differences, meaning some species have been lumped together, taxonomically speaking.

"Small, subtle differences in appearance are harder to notice when you're looking at a tiny animal that weighs 10 grams than when you're looking at something that is human-sized," explains biologist Bryan Carstens from Ohio State University.

"You can't tell they are different species unless you do a genetic analysis."

Scientists refer to these hidden species as 'biodiversity wildcards'. Unless we know they exist, we can't consider these creatures in evolutionary theory, food webs, or conservation work.

According to the most recent predictive models, over 80 percent of mammals have probably already received a formal classification. With more than 6,400 mammal species described on record, that would mean there are still over a thousand unknown species in need of formal classification.

Using machine learning to analyze gene sequences and geographic and biological data from over 4,000 mammals, researchers have identified which taxa are most likely to harbor hidden species.

By figuring out where these taxa usually live, the authors have helped highlight ecosystems for future taxonomic research.

Southeast Asia, for instance, is predicted to be a hub for unidentified mammalian species. Both evolutionary and genetic models estimate this region of the world contains the greatest proportion of diversity wildcards relative to species richness.

A study in Indonesia recently identified 14 novel shrew species, the largest haul of new mammals detailed in a single paper since 1931.

The current model found that around the world, most undescribed mammals fall into orders that include bats, rodents, and shrews and hedgehogs. These orders also tend to be found in wider geographic ranges with relatively high variability in temperature and precipitation, like tropical rainforests.

The results are what taxonomists have long suspected. Rainforests, in general, hold the most mammal diversity in the world, and since 1992, most newly described mammals have been small-bodied, found across large ranges and at home in habitats that experience daily and seasonal swings in rainfall and temperature.

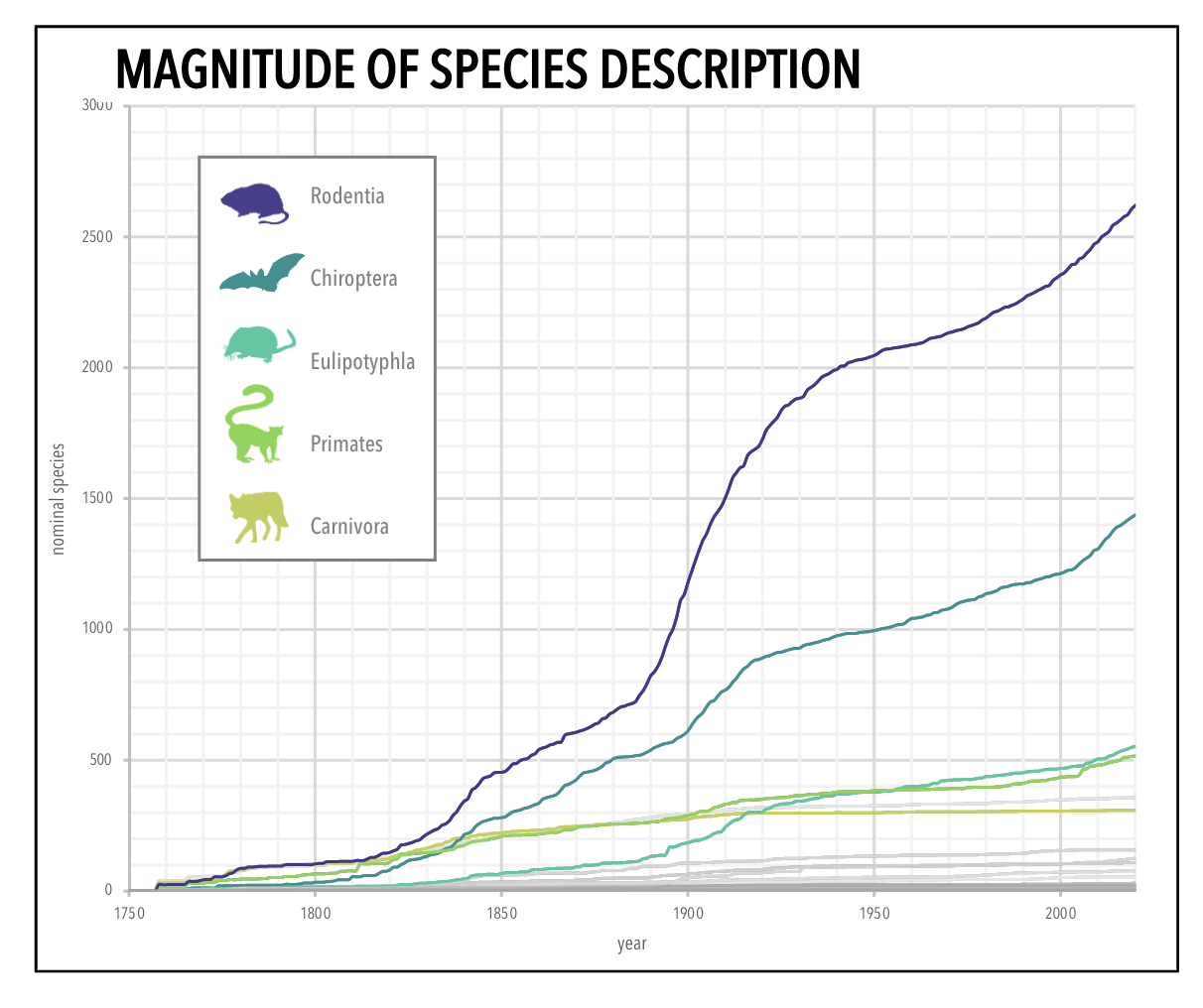

Species description rates across orders of mammals. (Parsons et al., PNAS, 2022)

Species description rates across orders of mammals. (Parsons et al., PNAS, 2022)

"Our study reinforces existing calls for a greater investment in taxonomic research, particularly in understudied and undescribed taxa facing quiet extinction," the authors write.

"It suggests that hidden species exist in predictable places, waiting for formal description."

History shows us that when humans put their minds to it, the tree of life grows ever more in focus.

After all, the reason why there is a larger portion of mammal species described than other orders is certainly not because invertebrate researchers are any worse at their jobs. Mammals are generally larger and easier to see. Plus, humans in general tend to be more interested in species that are more closely related to us, so mammals usually have more resources directed towards them.

Given what can be achieved with the right focus, the authors of the recent model are calling for renewed funding and interest in taxonomic research to close the gap between known and unknown mammal species.

"That knowledge is important to people who are doing conservation work. We can't protect a species if we don't know that it exists," says Carstens.

"As soon as we name something as a species, that matters in a lot of legal and other ways."

The study was published in PNAS.