Scientists have uncovered an extensive unmonitored trade of spiders, scorpions, and related species around the world. Many of these arachnids are wild caught, threatening these spectacular beasties with potentially unsustainable harvesting practices.

The team detected peaks in interest for these animals during COVID lockdowns.

"Trade in these groups exceeds millions of individuals," Suranaree University conservation biologist Benjamin Marshall and colleagues write in their paper detailing the extent of the trade. They explain that while the trade of some groups of animals is well known, other classes are completely overlooked, particularly invertebrates.

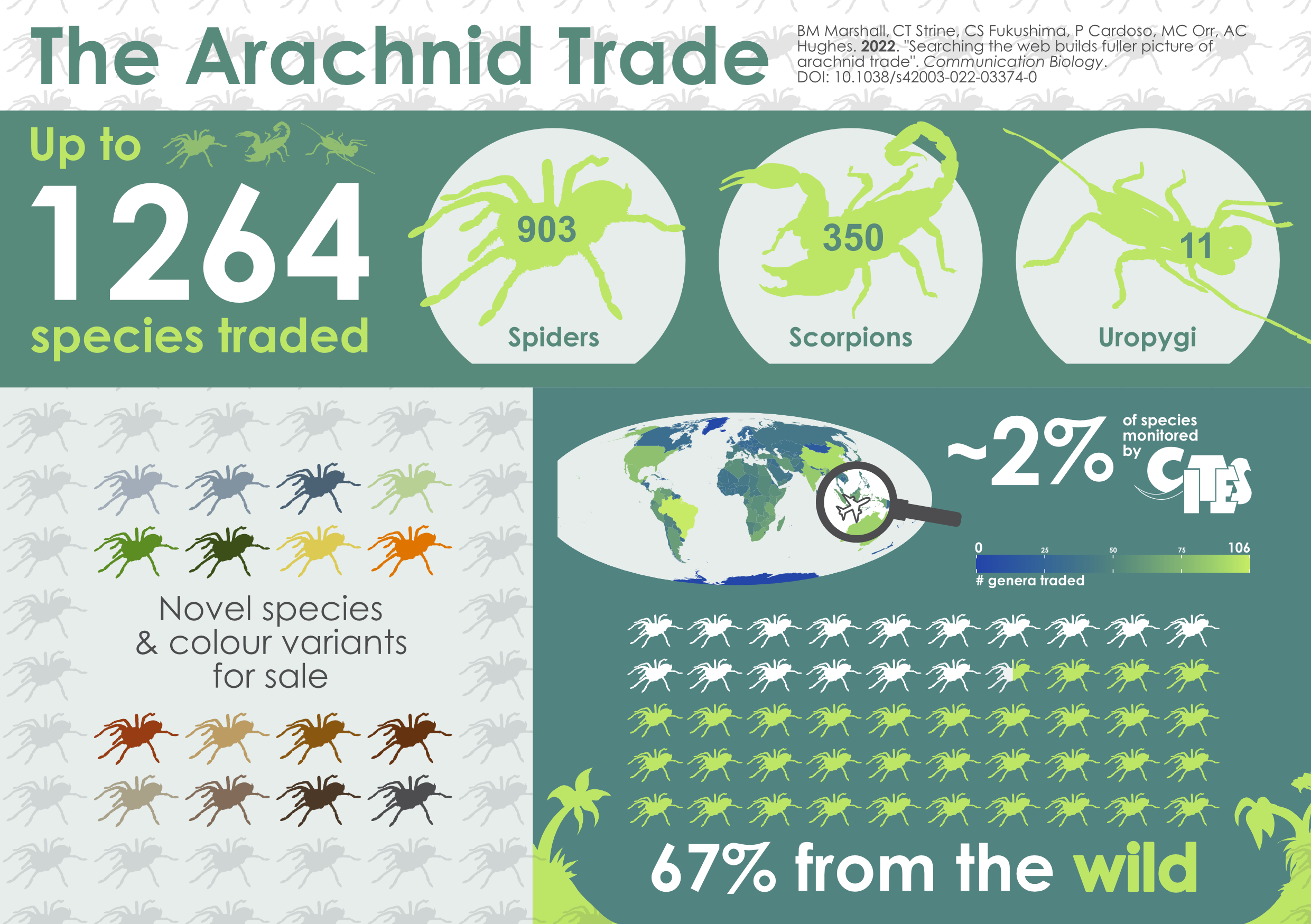

Trawling through online listings, the researchers discovered 1,264 different species up for sale. This is likely to be an underestimation, as they only searched through a subset of languages and didn't hunt through social media where trade is also known to take place.

Most of these species (more than 70 percent) are not recognized as ones being traded by any regulatory body. In contrast, most reptiles being sold are listed as such on LEMIS (US Fish and Wildlife Service's Law Enforcement Management Information System) and CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

They even found a single collector with 205 species of spider.

Colorful captive tarantula eating feeder worm. (Bry Wark/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

Colorful captive tarantula eating feeder worm. (Bry Wark/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

"Over 25 percent of tarantulas described since 2000 are already in trade," the team explains, "and a lack of regulations mean that even undescribed species can be exported without oversight."

The dazzling variety of large fuzzy tarantulas are highly sought after (which may come as a surprise to arachnophobes). But animals like tarantulas are of particular concern because they have traits that are well known to make species more vulnerable – such as long lifespans (up to 30 years).

With our world sorely needing more of us to be better connected with the world beyond humans, pets can help to encourage this connection, and they really benefit our own health too. Even the creepy crawly ones.

But taking on the responsibility of caring for any animal requires a lot of work even before you acquire them. This is especially true for so-called exotic animals, particularly if their trade is unregulated – because if you get it wrong, you risk directly contributing to the extinction in the wild of the animal you so value. Or even unintentionally causing the animal's untimely death.

Many species of arachnids are desired for their unique traits and colors, which means they're likely to be rarer.

"Wildlife trade is a major driver of biodiversity loss," say the authors. "Recent analysis has highlighted that pet trade represents a major potential threat to much greater numbers of species than previously realized, with 36 percent of reptiles and 17 percent of amphibians in trade, with around half individuals sourced from wild populations."

Regulating trade of invertebrates is especially challenging though, as their small sizes make them so easy to smuggle – often through regular postal services. They also aren't detected by X-ray and thermal scans. There's even "how to mail baby spiderlings" advice online.

Another huge problem is that there's still so much we do not know about these animals. We're missing even the most basic details on them, like their life histories and their ecological roles (such as what they eat), let alone their range and conservation status. Some arachnid groups, like scorpions, don't even have a centralized database of species names.

Only 1 percent of the over 1 million described invertebrate species have been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and almost 30 percent of those don't have enough data to draw a conclusion on the conservation status.

Of the species Marshall and colleagues found for sale, only 2 percent were listed on the CITES. But given the lack of data, this doesn't really tell us much at all about how many of the species being traded are endangered.

Much of the information they found was clearly inaccurate, with species origins often listed in places they're not actually native to and many species likely identified incorrectly.

(Marshall et al., Communications Biology, 2022)

(Marshall et al., Communications Biology, 2022)

"Existing regulations in most countries do not provide sufficient safeguards for most species," Marshall and team write. But they acknowledge that wide-scale regulation of wild caught species may be unrealistic given all the challenges.

"Lack of data on most species ranges means assessing vulnerability and developing appropriate management or conservation policies is currently impossible."

Instead, they propose that along with working on the regulatory side, switching to certified breeding programs would provide those looking to acquire these animals a way of doing so with minimal risk to wild populations. They suggest that DNA barcoding from feces samples may help with the issues of species identification.

"Whilst attempts to restrict trade are sometimes stated to contravene sustainable livelihood provision, unsustainable trade cannot provide stable economic gains in the long-term," Marshall and colleagues explain. This "ultimately undermines future access to that same 'livelihood' to other species which rely on them, and the ecosystem services they provide."

Our desire to admire and cherish the curious, strange, and beautiful life on this planet should not threaten their right to exist.

This research was published in Communication Biology.