Scientists have made a promising step forward in the ongoing fight against cancer, developing a new way to trigger cancer cell death that might eventually give us a new treatment option with better results than current methods.

Called Caspase-Independent Cell Death (CICD), it was able to completely eradicate tumours in colorectal cancer cells grown in the lab.

If the same effects can be reproduced in humans, then we could be looking at a treatment that can kill off cancers in a way that's less harmful to the body and with a lower chance of the cancer coming back, according to the team from the University of Glasgow in the UK.

"In essence, this mechanism has the potential to dramatically improve the effectiveness of anti–cancer therapy and reduce unwanted toxicity," says one of the researchers, Stephen Tait. "Taking into consideration our findings, we propose that engaging CICD as a means of anti-cancer therapy warrants further investigation."

Conventional anti-cancer treatments work by apoptosis, a kind of programmed cell death where cells effectively get ordered to kill themselves off, via proteins called caspases.

It's how chemotherapy works, for example, and it can work well – but there are caveats.

These therapies can miss some of their targets, which means cancer cells don't get eliminated and the tumours have a better chance of coming back, and can also be damaging to healthy cells, as anyone who's been through chemotherapy will tell you.

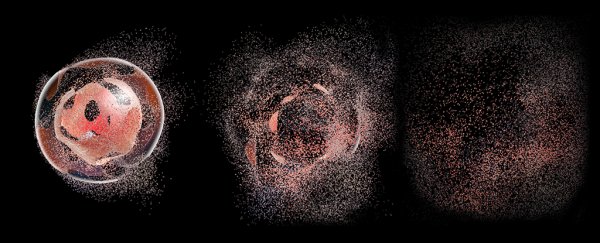

Enter CICD, which takes on some of the mechanisms of apoptosis but takes caspases out of the equation. When cells are killed off with CICD, the researchers found, they send a signal to the immune system that can then attack any remaining cancer cells.

It's a cleaner and hopefully safer way of taking a tumour out of a body – though it's worth emphasising that the treatment has only been tested on lab models so far.

"Especially under conditions of partial therapeutic response, as our experiments mimic, our data suggests that triggering tumour-specific CICD, rather than apoptosis, may be a more effective way to treat cancer," says Tait.

The hypothesis is that a therapy wouldn't have to kill off all the cancer cells itself, because the body's own immune system would swoop in and finish the job (cancer tumours are usually notoriously good at hiding from the immune system).

While these experiments focused on colorectal cancer, the researchers say it could be adapted to tackle different types of cancers too. That's one of the areas that will be investigated in future studies as scientists look to see if it could work in humans.

"This new research suggests there could be a better way to kill cancer cells which, as an added bonus, also activates the immune system," says Justine Alford from Cancer Research UK, who wasn't directly involved in the research.

"Now scientists need to investigate this idea further and, if further studies confirm it is effective, develop ways to trigger this particular route of cell death in humans."

The research has been published in Nature Cell Biology.