Incredibly well-preserved tracks of prehistoric baby elephants have revealed a crucial, ancient stomping ground for one of the largest animals to walk on Earth's surface since the dinosaurs.

On a beach in what is now southwest Spain, archaeologists have identified 34 sets of footprints belonging to the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus).

These huge land animals are long extinct but they once roamed through western Europe during the Late Pleistocene, more than 30,000 years ago. Standing up to 4.5 meters (15 feet) tall, they would have towered over modern day African elephants. They may have even been as large as the massive prehistoric rhinos that once travelled across Eurasia millions of years ago.

The ancient tracks of prehistoric elephants have been found in Europe before, but rarely do they include individuals quite so young as those represented in this new discovery, found in what is known as the Matalascañas Trampled Surface.

Using the length of each elephant track to estimate its height and weight, the team has found some of the youngest individuals were no more than two months old when they left their mark on the world.

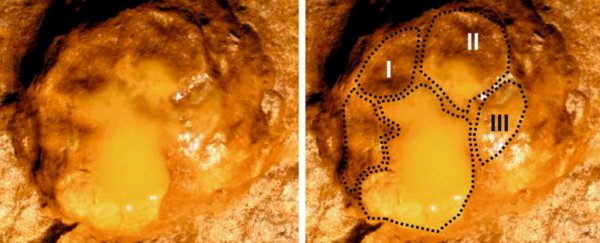

The footprint of an elephant calf at Matalacañas. (Neto de Carvalho et al., Scientific Reports, 2021)

The footprint of an elephant calf at Matalacañas. (Neto de Carvalho et al., Scientific Reports, 2021)

Altogether, the herd seems to have been made up of at least three mother elephants (over 15 years of age) and 14 newborn calves and adolescents.

Only two particularly large tracks could be linked definitively to adult bulls, standing over 3.25 meters high and weighing in at roughly 7 tonnes, which suggests the site was used primarily for reproduction by matriarchal groups.

Today, this possible former elephant nursery is nothing more than a beach, but thousands of years ago, researchers think the dunes would have housed the occasional pond, ringed by vegetation, which would have been an important source of food and freshwater - and not just for elephants.

Plenty of other animals have left their footprints in the clay here too, including dozens of Neanderthals both old and young, alone and in groups.

Neanderthal tracks. (Neto de Carvalho et al., Scientific Reports, 2021)

Neanderthal tracks. (Neto de Carvalho et al., Scientific Reports, 2021)

In fact, researchers say the dates of fossilized footprints from Neanderthals and elephants at this site overlapped on a short scale of time, which suggests the humans were there for more than just a drink.

Instead, the authors of the study suspect Neanderthals frequented this site to hunt or scavenge - not for the largest elephants, which would probably have been too risky, but for the weakened or dead individuals in the herd. They might even have waited for a mother elephant to go into labor before attacking.

Like modern elephants, straight-tusked elephant herds seem to have been led by females, and their groups tended to stick closer to water, as their young needed to drink more and could not move over vast distances as easily as their elders.

Artist's impression of a mother and baby straight-tusked elephant. (J. Galan)

Artist's impression of a mother and baby straight-tusked elephant. (J. Galan)

Early humans might have figured this out and waited for their moment to strike. Two of the tracks found actually look as though an older elephant was slowing its pace to protect a younger one next to it.

"Elephants are relatively easy to locate due to their dependency on water resources, reported use of familiar paths, and the clear tracks they leave behind," the authors write.

"There is an increasing amount of evidence that proboscideans [elephants], and especially young individuals, played a major role in Neanderthal's diet and adaptation."

Direct evidence of early humans hunting prehistoric elephants is rare, but the huge carcasses of these land mammals have been found butchered nearby human tools at some archaeological sites.

The findings of the new study support the hypothesis that even the largest land animals were once fair game for early humans, no matter their difference in size or strength.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.