The Wonderwerk Cave site in South Africa is one of very few places on Earth where human activity can be traced back continuously across millennia, and scientists just established the oldest evidence of archaic human habitation in the cave: some 1.8 million years ago.

That's based on an analysis of sedimentary layers containing animal bones, the remnants of burning fires, and Oldowan stone tools: Objects made from simple rocks with flakes chipped off to sharpen them, representing what was once a significant step forward in tool technology.

While tool artifacts at other sites have been backdated as far as 3.3 million years ago, the new findings are now thought to be the earliest sign of continuous prehistoric human living inside a cave – with the use of fire and tools in one fixed location indoors.

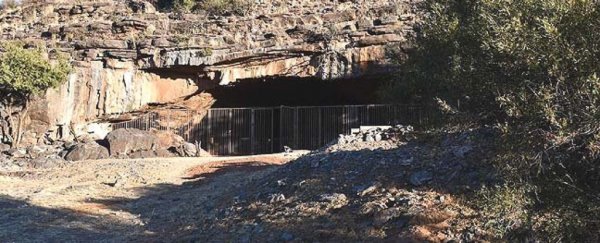

The Kalahari desert Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

The Kalahari desert Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

"We can now say with confidence that our human ancestors were making simple Oldowan stone tools inside the Wonderwerk Cave 1.8 million years ago," says geologist Ron Shaar from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

"Wonderwerk is unique among ancient Oldowan sites, a tool-type first found 2.6 million years ago in East Africa, precisely because it is a cave and not an open-air occurrence."

While ancient evidence of wildfires and human fires might get mixed up in open-air sites, that's not the case in the Wonderwerk Cave. What's more, other indicators of humans making fires were found: burnt bones and ash, for example, as well as the tools.

The sediment sample examined in the new study was 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) thick, charting hominin activity in the cave over time. Layers were dated in two ways, first through paleomagnetism, measuring the magnetic signal from clay particles that had drifted into the cave.

These signals, trapped in time, show the direction of Earth's magnetic field in history. As the variation and flipping of this field across the centuries can be charted, scientists can date the clay particles and everything deposited with them.

Secondly, the researchers used burial dating, an analysis of the radioactive decay of particles as they drift out of the glare of cosmic radiation and get buried underground, or, in this case, inside a cave.

Inside the Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Inside the Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

"Quartz particles in sand have a built-in geological clock that starts ticking when they enter a cave," says geologist Ari Matmon from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

"In our lab, we are able to measure the concentrations of specific isotopes in those particles and deduce how much time had passed since those grains of sand entered the cave."

As well as recording the use of Oldowan tools as far back as 1.8 million years ago, the team also spotted the transition to more complex hand axes (over 1 million years ago) and the first deliberate use of fire (around 1 million years ago).

While exciting discoveries continue to be made all across the world, very few places offer such a consistent record of ancient human comings and goings as the sediment layers inside the Wonderwerk Cave – as the new study shows.

"The precise ages of the Wonderwerk sediments are crucial for our understanding of the timing of critical events in hominin biological and cultural evolution in the region," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in Quaternary Science Reviews.