The body you inhabit is made up of lots of moving parts that need to communicate with each other.

Some of this communication – in the nervous system, for example – takes the form of bioelectrical signals that propagate through the body to trigger the appropriate response.

Now, US researchers have discovered that the epithelial cells that line our skin and organs are able to signal the same way to communicate peril. They just use a long, slow 'scream', rather than the rapid-fire communication of neurons.

It's a huge surprise, since these cells had been previously considered 'mute' – and may open new avenues for electrical medical devices to accelerate healing.

"Epithelial cells do things that no one has ever thought to look for," says polymath Steve Granick of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. "When injured, they 'scream' to their neighbors, slowly, persistently, and over surprising distances. It's like a nerve's impulse, but 1,000 times slower."

The body's communication networks keep it functioning. You'll whip your hand off a hot surface tout de suite without even thinking about it; that's your nervous system at work. Your heart's pumping action is regulated via electrical signals; the discovery of this enabled the invention of the artificial pacemaker.

Granick and his colleague, biomedical engineer Sun-Min Yu of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, designed a system to investigate cellular communication in the epithelium. Their system consisted of a chip connected to an array of around 60 electrodes.

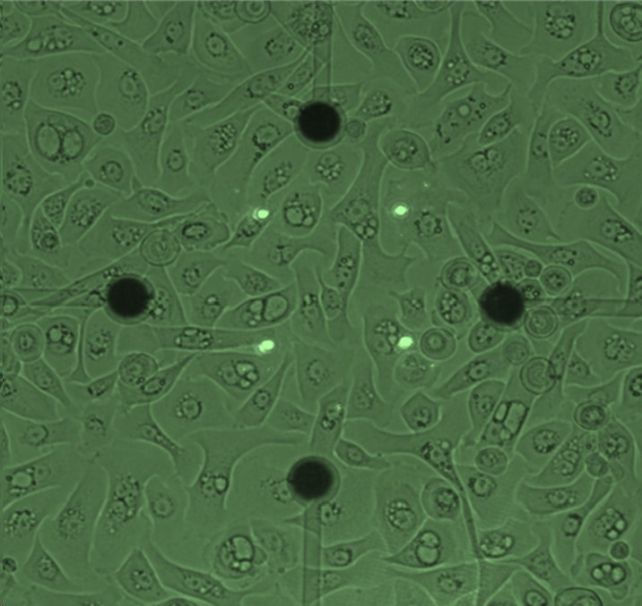

This chip was coated with a single layer of lab-grown human keratinocytes, the main epithelial cells that make up the epidermis, the outer layer of skin. With a laser, the researchers "stung" the skin layer, using the electrode array to listen in to the electrical shifts that followed.

"We tracked how cells coordinated their response," Yu says. "It's a slow-motion, excited conversation."

The resulting signals propagated at speeds of around 10 millimeters per second, across quite large distances up to hundreds of micrometers from the site of the wound. It seems not dissimilar to the electrical calcium signaling observed in plants when damaged by a hungry, hungry caterpillar, as seen in the video below.

This communication, the researchers observed, relied heavily on ion channels, small pores in cell membranes that allow the transport of charged ions, predominantly calcium.

In particular, these epithelial-cell ion channels respond to a mechanical stimulus, such as pressure or stretching, which is slightly different from the ion channels of neurons, which respond to changes in voltage or chemistry.

The epithelial signals last much longer than neuronal signals, too, with some "conversations" recorded for up to five hours, according to the researchers. However, the voltage was of a similar amplitude to that observed in neurons, and the communication cycled through the phases that neuronal communication does.

Because this is only a newly discovered phenomenon, more work needs to be conducted to understand how it works, and the different contributing factors.

We don't know for sure what the cells are using for the signal, or if different kinds of epithelial cells are operating differently when it comes to communicating harm, though initial tests suggest calcium ions are involved.

However, the discovery hints at new possibilities for biomedical devices, like wearable sensors and electronic bandages that accelerate wound healing.

"Understanding these screams between wounded cells opens doors we didn't know existed," Yu says.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.