We're facing a deadly Catch 22. As the world grows hotter, people crank up the air con. As they crank the air con, the world grows hotter. And so on. And so on.

If it seems like there's no escape from this gloomy, no-win situation, take heart: a new technology developed by scientists from the US and China could literally shine a light in the dark – and not just any dark either, but the cold emptiness of seemingly endless space.

Researchers at Stanford University have invented a new kind of solar panel technology that not only harvests light from the Sun and converts it into electricity (as conventional panels do), but can also beam excess heat into space at the same time.

"We've built the first device that one day could make energy and save energy, in the same place and at the same time, by controlling two very different properties of light," explains electrical engineer and senior author of the new research, Shanhui Fan.

(L.A. Cicero)

(L.A. Cicero)

The principle Fan is talking about is called radiative cooling, in which an object – any object, including buildings, or even your own body – emits heat in the form of infrared light.

When objects do this, they simultaneously lose heat by the process of thermal radiation, but while the phenomenon might seem like a great way of displacing Earth's impending heat problems, there's a catch: not all the emitted heat escapes our atmosphere and makes it into space.

"Think about the atmosphere as a big blanket around the Earth," one of the researchers, Zhen Chen, formerly of Stanford and now a professor at the Southeast University of China, told Fast Company.

"This blanket does not allow heat easily to go from the Earth to the cold universe. But there are 'holes' in the blanket, if you want to think about it that way, through which the heat can radiate out to outer space."

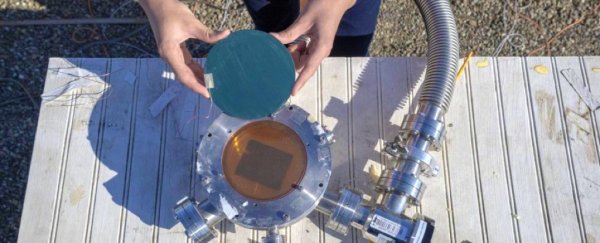

The new prototype the researchers developed is a first-of-its-kind attempt at combining a radiative cooling device with a conventional solar panel, creating a type of hybrid technology that both absorbs sunlight while emitting infrared light into the sky.

The unit is composed of a conventional solar absorber array about the size of a compact disc (if you remember those), which sits above a similar circle-shaped radiative cooler, made from silicon nitride, silicon, and aluminium layers enclosed in a vacuum.

The idea is that the solar panel is transparent for infrared, so while it should absorb most of the Sun's light, infrared light (with a wavelength between 8 and 13 micrometres) passes through it and can be emitted into space – to the extent it can navigate atmospheric 'holes' at least.

In testing, the device – which builds on the team's earlier radiative cooling innovations in 2014 and 2015 – succeeded as a proof of concept, with the bottom layer (the radiative cooler) recording lower temperatures than both the ambient air temperature and the solar panel.

(Chen et al/Joule)

(Chen et al/Joule)

"This shows that heat radiated up from the bottom, through the top layer and into space," Chen explains in a statement, although there's a lot more work to be done before this kind of double-duty solar panel could be installed on rooftops around the world.

For starters, the solar panel in the team's prototype wasn't actually functional in terms of producing electricity, which is the next problem for the researchers to solve: developing working solar cells with elements that don't block infrared light from boldly going where no one has gone before.

Once that technical hurdle is overcome, the sky is no longer the limit.

"It is widely recognised that the Sun is a perfect heat source nature offers human beings on Earth," says Chen.

"It is less widely recognised that nature also offers human beings outer space as a perfect heat sink."

The findings are reported in Joule.