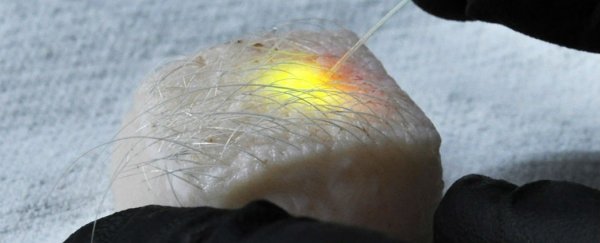

Two physicists have demonstrated a way to embed lasers into living human tissue using oil droplets and polystyrene beads to create microscopic mirrors. These droplets - less than the width of a human hair - can be induced to shine over different wavelengths and create a laser lightshow inside the skin.

This isn't some kind of radical body art project though - it's hoped the new technique will be used to better study cellular activity to figure out how tissues and molecules work together. "Right now, the technology is ready for applications in laboratory settings - to study cells and later to study their uses in small animals," Yun explained to Motherboard. "For example, [we use] the lasers to understand how cells move and respond to external force."

Because lasers have very narrow emission linewidths - each laser colour is distinctly separate on the spectrum - it means scientists can more easily target specific sets of cells and work out how they are behaving and the pressures on them. Further down the line, we might see lasers made completely of biological materials, according to Yun, although he admits they're not there yet.

By using separate polystyrene beads with different diameters, the team from Harvard Univesity's Wellman Centre for Photomedicine in the US believes they might even able to 'tag' individual cells within the body, and monitor thousands of cells at once, which could be seriously significant for treating diseases such as cancer and understanding more about how the human body works. Short pulses of light are required to activate the lasers, though most of the hard work is done by the beads themselves.

The report has been published in Nature Photonics.

One of the researchers, Seok-Hyun Yun, has previous work in this area: he was part of the team that created living lasers in jellyfish back in 2011. That process required the use of two external mirrors to create a microlaser, but this research goes a step forward by embedding everything needed to create a laser effect within the living tissue.

Pig skin cells were used in these most recent experiments, so you won't be getting a laser injection from your local doctor anytime soon, but academics agree that the research shows plenty of promise - eventually the process could be adapted to track as many cells as there are in the human body.