With COVID-19 cases continuing to rise around the world, scientists are doing everything they can to discover more about the virus that causes it - SARS-CoV-2 - as well as investigate potential vaccines to help us stop the spread.

SARS-CoV-2 has been incredibly effective at infecting and replicating in humans, but it doesn't spread so well in mice. This is good for mice, but not so good for scientists.

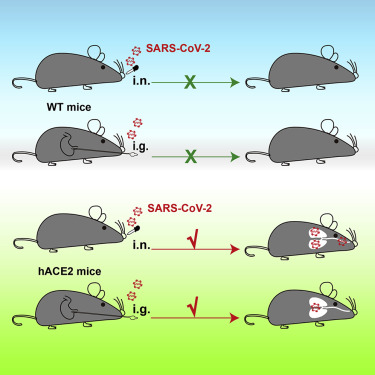

One of the important ways scientists develop and test new therapies is through experiments with mice. But when scientists try to infect a healthy, normal mouse with SARS-CoV-2, the animal doesn't contract the disease.

This means that scientists can't use mice as a stand in for humans to test potential vaccines, or investigate the virus in more invasive ways.

"A small animal model that reproduces the clinical course and pathology observed in COVID-19 patients is highly needed," says one of the researchers You-Chun Wang of the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (NIFDC) in China.

But there's good news. In a new study, a team of Chinese researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 to create mice with a human receptor on their cells called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2).

This is the receptor that SARS-CoV-2 uses to piggyback a ride into human cells - and it means that the virus can now infect mouse cells.

Once they had mice with the right receptor, the mice were infected through the nose with SARS-CoV-2, and the researchers saw replication of the viral RNA in their lungs, trachea, and brain.

"The presence of viral RNAs in brain was somewhat unexpected, as only a few COVID-19 patients have developed neurological symptoms," says one of the researchers, Cheng-Feng Qin of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences (AMMS) in Beijing.

(Sun et al., Cell Host & Microbe, 2020)

(Sun et al., Cell Host & Microbe, 2020)

The team also found that they could infect the mice through the stomach, mimicking the gastrointestinal issues sometimes seen in human infections - although the dose had to be 10 times as high as those entering the nose to cause an infection.

"Although fatalities were not observed, interstitial pneumonia and elevated cytokines were seen in SARS-CoV-2 infected- aged hACE2 mice," the team write.

This isn't the first time researchers have used hACE2 to try and create a COVID-19 mouse, but the team says their model has several benefits.

Firstly, the new model removes the mouse version hACE2, by replacing the mouse receptor gene with the human version in the exact specific location on the X chromosome.

"Secondly, the tissue distribution of hACE2 in our mouse model matches the clinical findings from COVID-19 patients, and high level hACE2 expression were detected in lung," the team write.

The team hopes that other researchers will use this same method and that it will eventually provide them with a way to investigate COVID-19 inside an animal model.

"The hACE2 mice described in our manuscript provide a small animal model for understanding unexpected clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans," says researcher Chang-Fa Fan of NIFDC.

"This model will also be valuable for testing vaccines and therapeutics to combat SARS-CoV-2."

The research has been published in Cell Host & Microbe