Researchers have converted induced pluripotent stem cells - cells capable of turning into any other type of cell - into pancreatic beta cells that can respond to glucose; when transplanted into diabetic mice, these cells blocked the condition altogether.

While the process has yet to be tested in humans, the results are exciting, because the hallmark of diabetes is a loss of functioning beta cells. If we can figure out how to transplant new, healthy beta cells into diabetes patients, we're looking at an actual cure, not just a treatment. "This discovery will enable us to produce potentially unlimited supplies of transplantable cells derived from a patient's own cells," lead researcher Ronald Evans told ABC News.

Diabetes, simply put, involves the loss of functioning beta cells in the pancreas: either these cells die (type 1 diabetes) or they don't do as they're told (type 2 diabetes), and in both cases, it leads to a lack of insulin to regulate the glucose levels in the blood. For a long time, scientists have been trying to replace these damaged or dead beta cells with healthy ones, and it finally looks as though they might have cracked it (in mice, at least).

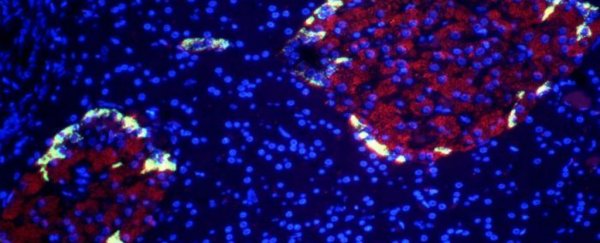

When researchers at the Salk Institute in California transplanted these human beta cells into mice with type 1 diabetes, the diabetes symptoms disappeared. In this case, the scientists depressed the immune systems in the mice to prevent the human tissue from being rejected, but this would probably be unnecessary in human trials, if the beta cells could be developed from a patient's own stem cells.

The research built upon several similar experiments, but the 'secret sauce' added this time around was a protein complex called Estrogen Related Receptor-gamma (ERRγ), which acted as the 'energy switch' required to get cells to grow out of the pre-beta stage and actually respond to surrounding glucose levels, rather than just producing insulin indiscriminately.

"This work transitions us to a new era in creating functional beta cells at will," Evans told the ABC. "In a dish, with this one switch, it's possible to produce a functional human beta cell that's responding almost as well as the natural thing."

There are reasons to be hopeful about these results and reasons to be cautious, but we'll start with the bad news.

As promising as the new study is, it's unlikely to be able to cure all cases of diabetes. One reason for this is that the disease is sometimes associated with genetic problems, which would mean it could probably restart itself even after new cells were transplanted. Secondly, type 2 diabetes is harder to tackle, because the new cells would be competing with the misfunctioning beta cells that are already in the body.

The good news is the chances of patients rejecting the new beta cells would be low, as they could be grown from their own cells. Plus for these experiments, the researchers used stem cells grown from regular skin cells, not the embryonic stem cells that are causing so many ethical and legal complications.

The bottom line is growing these cells shouldn't prove too much of a challenge and should remain affordable, but the big question is how a human diabetes patient will respond. Evans and his team are now working towards getting the technique ready for human trials in the coming years. Hopefully this is the start of something big.

"Hopefully, this mirrors what would happen in the clinic - after someone is diagnosed with diabetes they could potentially get this treatment," Evans said in a press statement. "It's exciting because it suggests that cells in a dish are ready to go."

The research team's findings have been published in the journal Cell Metabolism.