Whether you're a student trying to memorise facts for an exam, or a new staff member getting to grips with the ins and outs of a new job, we're continually trying to hold onto new information, while making sure we don't forget the important things we'll need to know later.

But what about the opposite situation: can we intentionally forget things too, using a process of reverse memorisation? According to a new study, we can, with scientists in the US saying brain scans of people being told to disregard certain information reveal the "neural signature" of intentional forgetting.

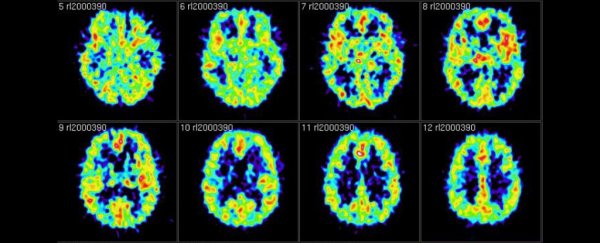

Researchers from Dartmouth College and Princeton University used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 25 participants as they engaged in a memory experiment.

The group was shown images of outdoor scenery – including scenes like forests, mountains, and beaches – as they studied two lists of random words.

"Our hope was the scene images would bias the background, or contextual, thoughts that people had as they studied the words to include scene-related thoughts," said lead researcher Jeremy Manning from Dartmouth College. "We used fMRI to track how much people were thinking of scene-related things at each moment during our experiment. That allowed us to track, on a moment-by-moment basis, how those scene or context representations faded in and out of people's thoughts over time."

After studying the lists of words interspersed with the scenery images, the participants were told to either forget or remember the words contained in them. When told to forget the words on one of the lists, the fMRI scans showed that the brain activity associated with the context of those words – the accompanying visual scenery – was 'flushed out'.

"It's like intentionally pushing thoughts of your grandmother's cooking out of your mind if you don't want to think about your grandmother at that moment," said Manning. "We were able to physically measure and quantify that process using brain data."

When the participants were instructed to remember the words on the list, the flushing out of scene-related thoughts didn't show up in the fMRI scans. But when they were directed to forget, the extent to which the scenery thoughts were flushed out predicted how well the participants remembered the words on a test taken after the scans.

The researchers acknowledge that visual scenery is not the only kind of contextual memory functioning in the brain, but given the limits of what scientists can track from scans of brain activity, it's one way of monitoring the forgetting process.

"[E]ach participant will have their own idiosyncratic constellation of slowly drifting thoughts. In our study, we focused on the level of scene activity as an indicator of contextual change because we purposefully 'injected' scene activity into participants' mental context… and we have sensitive tools for measuring scene activity with fMRI," the authors write in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

"If we had a way of identifying and tracking other kinds of context that were present during [memorisation of the list]," they add, "we would expect to see a similar decrease in these other kinds of contextual activity in response to the forget cue."

The team isn't claiming that their research pins down the exact mechanism by which our brains intentionally forget, but they have a few ideas.

It's possible, they suggest, that upon being instructed to forget something, people change their mental contexts by trying to think of new, unrelated thoughts that 'push out' the old contextual information. It's possible too that people may be able to suppress thoughts somehow without recalling other memories.

While it's only a very small study and one centred around a fairly elusive concept, the findings could hold promise for further research into intentional forgetting – especially as seeing that not remembering things can sometimes be a positive.

"[M]emory studies are often concerned with how we remember rather than how we forget, and forgetting is typically viewed as a 'failure' in some sense, but sometimes forgetting can be beneficial, too," said Manning. "For example, we might want to forget a traumatic event, such as soldiers with PTSD. Or we might want to get old information 'out of our head,' so we can focus on learning new material. Our study identified one mechanism that supports these processes."

There's an awful lot of research being conducted into what it is that makes people forget things. Earlier in the year, researchers in the UK reported how inhibitory connections called anti-memories work to silence our memories to help stabilise brain processes.

There's also been a considerable amount of studies on chemical aids to block memories, including recent research involving a drug that can disrupt memories associated with methamphetamine use, which could prove a big help to people trying to recover from drug addictions.

For more on the science of forgetting things on purpose, check out this video.