We're social animals, people. Over the course of thousands of years of evolution, we've found it easier to survive by sticking together, which makes it more likely we'll find vital resources like food and shelter. Without companionship for long periods, we don't feel well emotionally – perhaps because it's more dangerous for us to be alone.

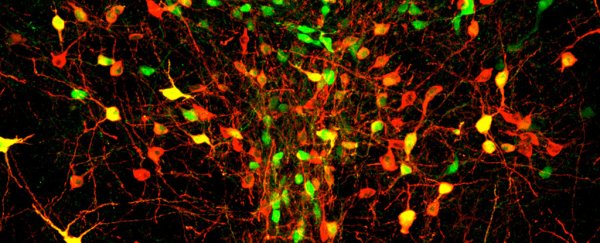

Now, for the first time, scientists in the US have identified the brain region that represents these feeling of loneliness. In a study of mice, neuroscientists pinpointed a cluster of cells near the back of the brain, in an area called the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). According to the researchers, this neural circuit is what motivates social animals to seek out the company of others after periods of isolation.

"To our knowledge, this is the first time anyone has pinned down a loneliness-like state to a cellular substrate," said neuroscientist Kay Tye from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). "Now we have a starting point for really starting to study this."

The findings, reported in Cell, are important because, while much research has looked at how the brain seeks out and responds to social interaction, we know comparatively little about how isolation and loneliness themselves motivate our social behaviour.

"There are many studies from human psychology describing how we have this need for social connection, which is particularly strong in people who feel lonely," said one of the researchers, Gillian Matthews. "But our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying that state is pretty slim at the moment."

The researchers first noticed DRN changes in mice brains in separate experiments involving drug testing, which required the animals to be isolated. They found that following a period of isolation, there was a strengthening of connections in the DRN. Subsequent tests showed that DRN neurons were not very active when the animals were housed together, but their activity surged after mice were reunited with one another.

When the team suppressed the DRN neurons using light, they found that isolated animals did not show the same level of rebound in sociability when reunited with their compatriots.

"That suggested these neurons are important for the isolation-induced rebound in sociability," said Tye. "When people are isolated for a long time and then they're reunited with other people, they're very excited, there's a surge of social interaction. We think that this adaptive and evolutionarily conserved trait is what we are modelling in mice, and these neurons could play a role in that increased motivation to socialise."

Interestingly, the more dominant an animal is in terms of group social hierarchy, the more responsive it seems to be to changes in DRN activity. In other words, socially dominant mice may be more susceptible to loneliness stemming from isolation.

"The social experience of every animal is not the same in a group," said Tye. "If you're the dominant mouse, maybe you love your social environment. And if you're the subordinate mouse, and you're being beat up every day, maybe it's not so fun. Maybe you feel socially excluded already."

According to Alcino Silva, a neurobiologist and psychiatrist from the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved with the research, the findings represent a new cornerstone for future studies of loneliness, and they could help us understand a range of social impairments – including social anxiety and autism spectrum disorders.

Of course, until scientists can identify similar effects in DRN neurons in human brains, we won't know for sure that these findings apply beyond mice – but it's a promising area for future research.

"There is something poetic and fascinating about the idea that modern neuroscience tools have allowed us to reach to the very depths of the human soul," said Silva, "and that in this search we have discovered that even the most human of emotions, loneliness, is shared in some recognisable form with even one of our distant mammalian relatives – the mouse."