As the world's population continues to grow, so too does the strain on the environment. Not least among the stressors is food production, especially the vast swathes of land and water required for the cultivation of livestock.

It's still in its infancy, but lab-cultured meat could be one means of easing the pressure – and Korean scientists have just found an innovative way to make it. They've invented a new hybrid food, consisting of cells of bovine fat and muscle grown inside grains of rice.

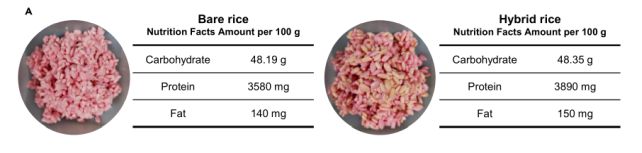

The result resembles a strange combination of meat mince and rice, of pink, sticky grains. But according to a team led by biomolecular engineer Sohyeon Park of Yonsei University, the mash-up is rich in nutrition, and although a little labor-intensive to produce now, could one day ease food pressure.

"Imagine obtaining all the nutrients we need from cell-cultured protein rice," Park says. "Rice already has a high nutrient level, but adding cells from livestock can further boost it."

Rice is about 80 percent starch, with the remaining 20 percent being protein and other nutrients. It's an excellent dietary staple, but the researchers thought there might be a way to make it work a little harder.

In biological systems, cells require a scaffolding that shapes tissue as it grows. In laboratory settings, scientists often use an artificial matrix for various tissues and organs. Park and her colleagues thought being so porous, rice could serve the same function, acting as the scaffold on which lab-grown animal cells can build into tissue.

First, they coated grains of rice with food-grade fish gelatin and food enzymes to help the cells find purchase and maximize the amount of cellular material that clings to and grows on the rice. Then they seeded the rice grains with cow muscle and fat stem cells, and let them grow in a petri dish for 9 to 11 days.

At the end of the cultivation period, the researchers tested the rice to study its structure and nutritional content. They found that the beef-rice hybrid was both firmer and more brittle than regular rice.

More to the point was how the nutritional profile of the rice changed. The hybrid rice had significantly higher protein and fat content – 8 percent more protein and 7 percent more fat – than untreated rice. That might not seem like a lot, but with tweaking it could be bumped even higher. As it stands, the meaty-rice (or ricey-meat) would be less costly to produce than beef per gram of protein, in both emissions and money.

Hybrid rice production, the team calculated, produces 6.27 kilograms (13.82 pounds) of carbon dioxide per 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of protein. Beef releases 49.89 kilograms of carbon dioxide per 100 grams of protein. And the cost of hybrid rice to the consumer would be around 15 percent of the price of beef per kilogram.

And the changes to the flavor profile of the rice could be interesting too. The team found that beef muscle and fat added different odor compounds to the rice, which could be fun for cooks to experiment with.

What remains now is to refine the production process to reduce the time it takes to make hybrid rice. The team may also experiment with maximizing the uptake of cellular material into the rice grains, which are remarkably receptive to the process.

"I didn't expect the cells to grow so well in the rice," Park says. "Now I see a world of possibilities for this grain-based hybrid food. It could one day serve as food relief for famine, military ration, or even space food."

The research has been published in Matter.