Researchers have discovered a way to consistently induce the same visual hallucination in healthy people - without drugs.

The DIY trip can be induced from anywhere by watching a short video, and causes people to all see the same hallucination - moving grey blobs.

That means scientists can begin to study exactly what causes hallucinations in the brain, and how to treat them in people with conditions such as Parkinson's disease.

And, yes, you can try it for yourself using the video below.

Although many people associate hallucinations with psychiatric disorders, healthy people can also experience them after taking drugs, when they're sleep deprived, or suffering migraines. Hallucinations can also be triggered by conditions such as Parkinson's disease, and researchers struggle to control them.

It's thought that these involuntary experiences arise when changes occur in the brain, causing it to temporarily hijack visual function - but the exact mechanisms aren't understood.

That's because, in order to study hallucinations, researchers need a large group of people all undergoing the exact same hallucination at the same time, from the same trigger - and no one has been able to do that, until now.

A team from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Australia has upgraded an old hallucination trick, using flashing lights to stimulate consistent hallucinations.

"We have known for more than 100 years that flickering light can cause almost anyone to experience a hallucination," said lead researcher Joel Pearson from UNSW. "However, the unpredictability, complexity and personal nature of these hallucinations make them difficult to measure scientifically."

In the past, flashing lights would trigger hallucinations that would differ across each person - they'd all report seeing different colours and different shapes, so it was hard to figure out exactly what was going on.

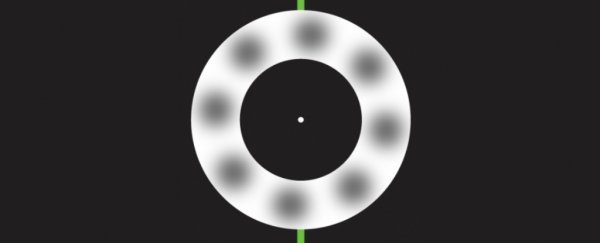

But the new technique uses a flickering white light against a black backdrop, and it triggers the exact same hallucination in the almost 100 healthy student volunteers tested so far, causing them to 'see' pale grey blobs that aren't really there. The circle is actually just white, which you can see if you pause the video.

You can watch the video below to see if it works for you, but it's recommended that anyone with a history of migraines, epilepsy or psychiatric disorders avoid it:

After staring at the screen, you should see pale grey blobs appear in the ring and rotate around it, first in one direction and then the other. But it's worth noting that although this has worked on all students it's been tested in so far, there's no guarantees it'll work for everyone.

"With our technique we get rid of the unpredictability," said Pearson. "People don't see windmills, lines, or different colours; they just hallucinate grey blobs. Once the hallucination is stable like this, with just the blobs, we can start to objectively investigate the underlying mechanisms."

"Nobody has been able to do this before, because they haven't been able to overcome this key challenge," he added.

Using this video, the team was able to objectively measure the strength of people's hallucinations, by placing a second ring marked with permanent grey blobs inside the white ring, and asking participants if the ones they hallucinated were darker or lighter than the real ones.

Joel Pearson

Joel Pearson

They then took the study one step further and performed the same technique, but by alternating the flashes of light into either the left or right eye, one at a time.

The fact that the students were all able to see the hallucinations when this happened confirmed that the hallucinations were arising in the visual cortex - the region of the brain that processes visual data and allows us to see, and the only part of the brain that can piece together messages coming in from the left and right eye separately.

In fact, the hallucinations seem to obey many of the same laws and properties as normal visual perception, said Pearson, which gives the team important clues on how to prevent them happening in patients in future.

The next step will be to test the new technique in patients with Parkinson's disease - something the team is planning to start immediately.

We're looking forward to what this new research can teach us about how our brains process images, and figure out what's real and what's not.

The research has been published in eLife.

UNSW Science is a sponsor of ScienceAlert. Find out more about their world-leading research.