A new study has found evidence that brain tumours use fat as their preferred source of energy, bringing into question the decades-long assumption that sugar is their main fuel source.

If confirmed, this could fundamentally change the we treat cancer in the future, because until very recently, scientists have been focussing their efforts on ways to starve cancer cells of their sugar supply.

"For 60 years, we have believed all tumours rely on sugars for their energy source, and the brain relies on sugars for its energy source, so you certainly would think brain tumours would," lead researcher Elizabeth Stoll, a neuroscientist from Newcastle University in the UK, told Ian Johnston at The Independent.

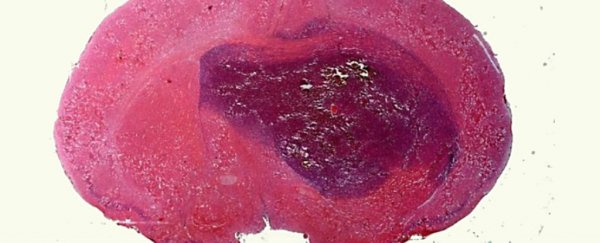

A glioma is a type of brain tumour that grows from glial cells - cells that support the neurons and help maintain the blood-brain barrier. Glial cells make up 90 percent of the brain's total cells, and until recently have been shrouded in mystery.

There are three types of glial tumours - astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and glioblastoma - and they can be notoriously difficult to treat. Glioblastomas are the most common and most aggressive form, with just 30 percent of patients in the US living to more than two years after diagnosis.

A new target for treatments could make a huge difference, with Stoll and her team finding that when they inhibited the tumour cell's ability to process fat as fuel, their growth rate slowed significantly, which equates to a better survival rate.

The team worked with human tumour tissue that had been donated by glioma patients undergoing surgery, and live mouse models of the disease, and treated them with a fatty acid oxidation inhibitor called etomoxir.

"We tested etomoxir in our animal model, and showed that systemic doses of this drug slow glioma growth, prolonging median survival time by 17 percent," Stoll said in a press statement. "These results provide a novel drug target which could aid in the clinical treatment of this disease for patients in the future."

The idea of cancer growth being fuelled by glucose - a simple sugar that healthy cells also break down to use as an energy source - has been around since at least the 1950s, when Nobel Prize-winning German scientist Otto Warburg observed that tumours primarily metabolised glucose in order to grow.

This process, known as the Warburg effect, and is now estimated to occur in up to 80 percent of cancers.

"It is so fundamental to most cancers that a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which has emerged as an important tool in the staging and diagnosis of cancer, works simply by revealing the places in the body where cells are consuming extra glucose," Sam Apple reports for The New York Times.

With so many cancers appearing to reply on glucose first and foremost for their growth, and healthy brain cells themselves also relying on sugar to keep functioning, it was only natural for scientists to assume that cancer cells in the brain would follow suit.

This perception was also perpetuated by the way scientists treat tissue samples in the lab.

As Stoll explained to The Independent, it's common for researchers to extract brain tumour cells from patients and put them into blood to culture them in the lab. But the simple act of placing these cells into a medium where sugar is more abundant than fat appears to change them, prompting them to switch fuel sources and use sugar because they're starved of fat.

Stoll's team avoided this complication by culturing their mouse and human tumour cells in serum-free conditions.

"What we have always needed to do is put the cells in [blood] serum. It's a trick to get the cells to grow in culture," she said. "If you take malignant brain tumours and expose them to blood serum, it changes them. Then they switch quite easily."

We should make it clear that Stoll's discovery has so far only been made in animal models and extracted human brain tumour cells, so until the team can demonstrate similar effects from the drug etomoxir in human trials, we can't jump to any conclusions.

The researchers also say they're not ready to make any assumptions about how our diets could be implicated in the fat versus sugar debate at this stage.

But any new target for cancer research is something to be cautiously optimistic about, because if anything is going to allow us to finally beat the enigma that is cancer, it's going to be a better understanding of what fuels its relentless growth.

The results have been published in Neuro-Oncology.