Beneath the rocky soil of Morocco, researchers have uncovered a surprising intruder living undetected inside termite colonies.

Few outsiders gain acceptance in termite society, but a species of blowfly has evolved an incredible multipart disguise that successfully fools termites, allowing its larvae to not just survive but seemingly thrive.

This has not been firmly documented previously in these flies, according to a new study. The authors say it was luck they discovered the fly larvae inhabiting colonies in the Anti-Atlas mountains of southern Morocco, where native harvester termites (Anacanthotermes ochraceus) build subterranean nests.

Evolutionary biologist Roger Vila from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Spain and his team study butterflies and ants, and since few butterflies were active that day due to recent rains, they looked for ants.

"When we lifted a stone we found a termite mound with three fly larvae that we had never seen before," Vila says. "The water had probably flooded the deeper layers of the nest and the larvae had emerged onto the surface."

Intrigued, the researchers returned three times. They lifted hundreds of stones but found only two more of the larvae, which were together in a termite mound.

This suggests the species is rare, Vila says. Phylogenomic analysis indicates the blowflies belong to the genus Rhyncomya, although more research is needed to investigate its abundance, along with other details about its biology and ecology.

What we know so far is already astounding, though.

Termites use their antennae to pat down and smell anyone who enters, helping them quickly identify trouble. Specialized soldier termites have giant mandibles for just such an occasion.

Yet with such enviable safety, climate control, and food security, it may be tempting for other insects to try infiltrating their colonies, despite the risk.

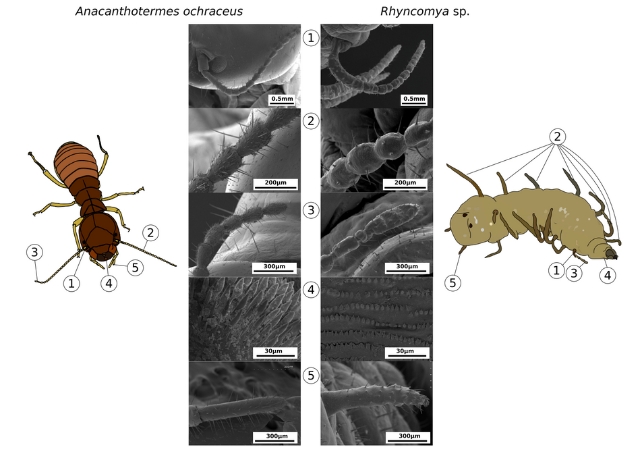

For part of their disguise, the blowfly larvae display a "termite mask" on their rear end. This consists of a fake head adorned with antennae and palps similar to those of a harvester termite.

The fake head also includes fake eyes, which look remarkably like harvester termite eyes. In reality, Vila notes, these are breathing holes.

"Most termites live several meters deep and have no visual perception," Vila says. "However, harvester termites come out at dusk to collect grass, so they have functional eyes that the larvae are able to mimic with their spiracles."

In addition to the fake termite head, larvae's bodies are covered with strange 'tentacles'. These are uncanny imitations of termite antennae, as the researchers demonstrated with scanning electron microscopy.

Unlike the fake head, these tentacles may be functional. The flies seem to actually use them for communicating with termites.

And since the larvae have so many of these protrusions, they're able to communicate with several termites at once.

Those are both impressive adaptations, but still not quite enough on their own.

Each termite colony has its own scent, shared by all members, and nobody gets in without it. Looking like a termite won't help if you don't smell right – intruders from other colonies are not welcome, and may be dismembered by soldiers.

But these fly larvae are pros. They don't just imitate a colony's scent; according to Vila, they match it perfectly.

"We quantified the chemical composition of these larvae and the result is surprising: They are indistinguishable from the termites in the colony where they live; they smell exactly the same," he says.

In the wild, the fly larvae had been in their hosts' food chambers when Vila and his colleagues found them. The researchers brought some back to a laboratory termite mound, where the larvae gravitated toward more populated areas.

Termites were highly attentive, flocking around the fly larvae and preening them. They also appeared to feed them.

"The larvae are not only tolerated, but they constantly communicate with the termites through contact with their antenna-like tentacles," Vila says. "The termites even seem to feed them, although this has not yet been unequivocally demonstrated."

Some humpback flies (Phoridae) also mimic termites, but they do it as adults, not larvae. They're also not closely related to these blowflies, suggesting the ruses evolved independently.

"The common ancestor of blowflies and humpback flies dates back more than 150 million years, much further than that which separates humans from mice. We are therefore confident that we have discovered a new case of social integration evolution," Vila says.

No other known species in the genus Rhyncomya exhibit a similar appearance or lifestyle, hinting at a relatively quick evolution.

"This discovery invites us to reconsider the limits and potential of symbiotic relationships and social parasitism in nature," Vila says.

"But, above all, we should realize how much we still do not know about the vast diversity and specialization of insects, which are essential organisms in ecosystems."

The study was published in Current Biology.