Scientists say they have determined the most likely place to find traces of ancient microbial life on Mars in future missions to the Red Planet.

In a new 'field guide' for discovering fossils on Mars, researchers say iron-rich rocks located near the sites of ancient lakes should be the priority for upcoming visits to the Martian surface, because they are acting like mineral sanctuaries that could preserve signs of life from billions of years ago.

"There are many interesting rock and mineral outcrops on Mars where we would like to search for fossils, but since we can't send rovers to all of them we have tried to prioritise the most promising deposits based on the best available information," explains astrobiologist Sean McMahon from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Narrowing the field of focus isn't such a bad idea.

After all, in over 2,100 days of exploration, NASA's current Curiosity rover has covered just 18 kilometres (11 miles), and while the upcoming Mars 2020 mission will enjoy unprecedented manoeuvrability, knowing the optimal rock targets in advance gives us the best chance of hitting Martian pay-dirt.

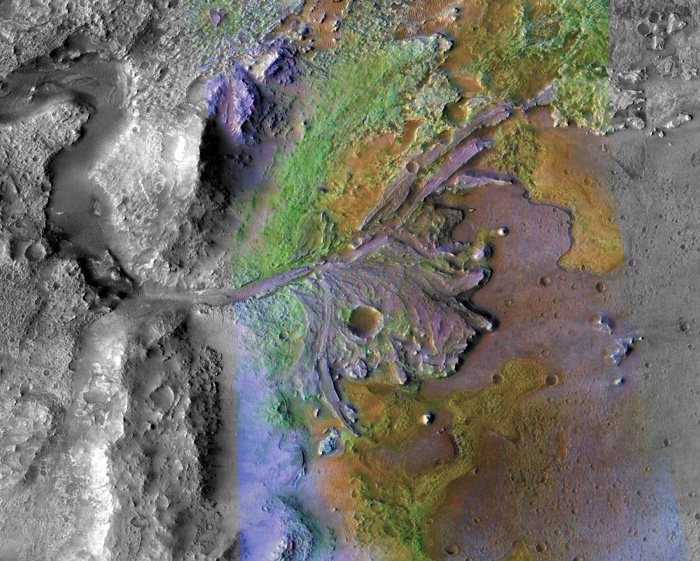

The Jezero Crater river delta on Mars (NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/JHU-APL)

The Jezero Crater river delta on Mars (NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/JHU-APL)

To that end, McMahon and his team reviewed scientific literature of rocks on Mars and the potential of their environments to preserve the remains of microbial organisms that could have once lived in them – based on what we know about fossils on Earth, and previous experiments replicating Martian conditions.

The findings suggest sedimentary rocks that formed in lake beds from compacted mud or clay are the most likely to contain fossils, due to their high iron and silica content.

"The Martian surface is cold, dry, exposed to biologically harmful radiation and apparently barren today," the authors explain in their paper.

"Nevertheless, there is clear geological evidence for warmer, wetter intervals in the past that could have supported life at or near the surface."

Specifically, the team thinks rocks that formed between the Noachian and Hesperian periods of the Red Planet's geological past – roughly 4 to 3 billion years ago – could have held onto the vestiges of Martian life that may have lived when the planet was wet.

"We recommend that iron-rich lacustrine mudstones, especially those rich in silica, should be prioritised for biosignature exploration," the researchers write.

"These rocks are present on Mars, represent aqueous environments with a range of redox states suitable for anaerobic metabolisms, and offer the possibility of preservation by silicification, clay authigenesis, clay-organic adsorption, and iron mineralisation."

The researchers acknowledge that just because ancient life could have become fossilised inside these sorts of rocks, there's no guarantee the fossils would still exist billions of years later – especially in light of weathering under Mars's hazardous non-atmosphere.

But they say since Mars is not subject to plate tectonics to the extent Earth is, metamorphism in underground rocks is significantly reduced, meaning there's a chance these ancient, fossil-bearing rocks could have survived.

Let's hope so, and while we're at it, fingers crossed Mars 2020 puts this field guide into action, so we get a chance to test the team's hypothesis. There's not too long to wait now.

The findings are reported in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.