With its scorching heat and corrosive atmosphere, the toxic hellhole that is Venus isn't the most inviting place in the Solar System, but if you do ever get the opportunity to visit, make sure to return before nightfall.

A new analysis of Venus's mysterious night side – the imperceptible dark half that faces away from the Sun – has unexpectedly revealed that the swirling Venusian atmosphere and powerful winds are even more chaotic when masked in shadow.

"This is the first time we've been able to characterise how the atmosphere circulates on the night side of Venus on a global scale," says astrophysicist Javier Peralta from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

"While the atmospheric circulation on the planet's dayside has been extensively explored, there was still much to discover about the night side."

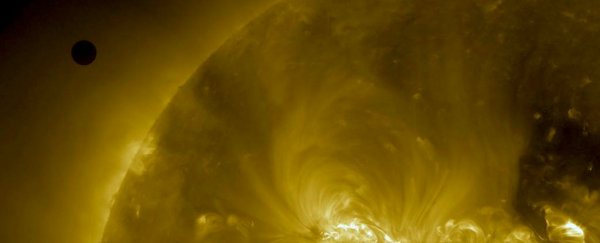

Super-rotation by night (left) and day (right). Credit: ESA, JAXA, J. Peralta and R. Hueso

Super-rotation by night (left) and day (right). Credit: ESA, JAXA, J. Peralta and R. Hueso

This mysterious stretch of darkness has been all the more puzzling due to its epic extent.

Venus only rotates once every 243 Earth days – the slowest turning of any planet in our Solar System – and there's a lot we don't know about what happens to its weather when the Sun goes down (for a long, long time).

To find out, Peralta's team peered into the Venusian dark using the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) on the ESA's Venus Express spacecraft, which orbited the planet between 2006 and 2014.

Venus's atmosphere is dominated by strong winds that swirl around the planet up to 60 times faster than the planet itself turns. This phenomenon is called 'super-rotation', which scientists have observed by tracking the movement of glinting clouds floating above Venus.

"We've spent decades studying these super-rotating winds by tracking how the upper clouds move on Venus's dayside – these are clearly visible in images acquired in ultraviolet light," says Peralta.

"However, our models of Venus remain unable to reproduce this super-rotation, which clearly indicates that we might be missing some pieces of this puzzle."

Cloud filaments. Credit: ESA, S. Naito, R. Hueso and J. Peralta

Cloud filaments. Credit: ESA, S. Naito, R. Hueso and J. Peralta

Thermal emissions had previously hinted at the movement of the uppermost clouds in Venus's atmosphere, but as for what was happening underneath the cloud canopy, scientists were none the wiser.

Thanks to Venus Express, we've now got a clearer picture.

"VIRTIS enabled us to see these clouds properly for the first time, allowing us to explore what previous teams could not," says Peralta, "and we discovered unexpected and surprising results."

Existing models of the atmosphere had predicted super-rotation largely occurred the same way on both Venus's day and night sides, but the new infrared perspective shows the whirling Venusian winds are actually more irregular and chaotic when hidden from the Sun.

The team's research shows that the night side produces large, wavy, and irregular clouds in filament-like patterns that aren't observed on the sunny side, and the team thinks a phenomenon called stationary waves is responsible.

"Stationary waves are probably what we'd call gravity waves – in other words, rising waves generated lower in Venus's atmosphere that appear not to move with the planet's rotation," says one of the researchers, Agustin Sánchez-Lavega from the University del País Vasco in Spain.

"These waves are concentrated over steep, mountainous areas of Venus; this suggests that the planet's topography is affecting what happens way up above in the clouds."

It's not actually the first time these gravity waves have been observed on Venus, but the new data suggest the phenomenon isn't solely restricted to elevated regions on the planet, such as mountains.

In the study, VIRTIS observed areas in the Venus's southern hemisphere, which is generally low in elevation, but the team says gravity waves still influence the atmospheric movements – but strangely enough, there was no evidence of them in the lower cloud levels, up to 50 kilometres (about 30 miles) above the surface.

As for why that is, the team isn't exactly sure. It seems that, while we're getting better at peering into the shadows, Venus definitely isn't giving up all it secrets just yet.

"We expected to find these waves in the lower levels because we see them in the upper levels, and we thought that they rose up through the cloud from the surface," says one of the team, Ricardo Hueso from the University of the Basque Country in Spain.

"It's an unexpected result for sure, and we'll all need to revisit our models of Venus to explore its meaning."

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy.