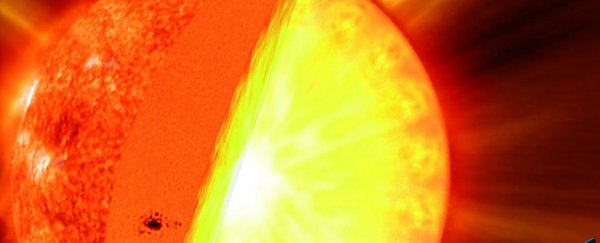

The innermost region of the Sun is hidden from our eyes, and it looks like this stealth has enabled the core to conceal a massive secret.

For the first time, scientists have been able to accurately measure the rotation of the solar core, revealing that it doesn't turn at the same speed as the surface – but rotates nearly four times faster.

While researchers had considered the possibility that the Sun's core rotation might not keep pace with its outer face, up until now there was no way of knowing for sure – and many assumed the whole Sun turned as one, like an integrated merry-go-round.

But the latest data, sourced by the ESA and NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), provides the first evidence of a kind of low-frequency gravity wave (g-wave, not the same thing as gravitational waves) reverberating through the Sun, which turned out to be the key to capturing the core's rotation.

ESA

ESA

"We've been searching for these elusive g-waves in our Sun for over 40 years, and although earlier attempts have hinted at detections, none were definitive," says astronomer Eric Fossat from the Côte d'Azur Observatory in France.

"Finally, we have discovered how to unambiguously extract their signature."

Up until now, scientists have been able to measure higher-frequency waves, called pressure or primary waves (p-waves), which pass through the upper layers of the Sun and are easily detected on the solar surface.

By contrast, g-waves oscillate deep in the solar interior, and while they can tell us about the behaviour of the core, they have no clear signature at the surface.

"The solar oscillations studied so far are all sound waves, but there should also be gravity waves in the Sun," Fossat explains, "with up-and-down, as well as horizontal motions like waves in the sea."

Using some 16 years' worth of SOHO observational data, the researchers were able to isolate a kind of g-wave called a g-mode, by analysing how long it takes a sound wave to travel through the Sun and back to the surface again: a trip known to be 4 hours, 7 minutes.

By combing through the readings, they uncovered a series of modulations – like a sloshing motion of underwater waves – that showed them how g-waves were shaking the Sun's core.

The results suggest that the Sun's core rotates in full about once per week, which is almost four times as fast as the solar surface and intermediate layers, which vary: rotating in 25 days at the equator, and 35 days at the poles.

"This is certainly the biggest result of SOHO in the last decade, and one of SOHO's all-time top discoveries," says Bernhard Fleck, SOHO project scientist from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre.

As for how this rotational discrepancy came about, the researchers' best guess is that it's a throwback to the Sun's very beginnings.

The thinking goes that somehow the radiation and solar wind projected from the Sun is in fact capable of slowing the orb's outer regions down – but it's a surface-only phenomenon that leaves the innermost core spinning undisturbed.

"The most likely explanation is that this core rotation is left over from the period when the Sun formed, some 4.6 billion years ago," says one of the team, astronomer Roger Ulrich from UCLA.

"It's a surprise, and exciting to think we might have uncovered a relic of what the Sun was like when it first formed."

All in all, it's a massive discovery for astronomers, and now that we've finally confirmed the presence of g-modes in the Sun after hunting for them for so long, the researchers say they're just getting started.

"It is really special to see into the core of our own Sun to get a first indirect measurement of its rotation speed," Fossat says.

"But, even though this decades-long search is over, a new window of solar physics now begins."

The findings are reported in Astronomy & Astrophysics.