Tuberculosis has plagued humanity for thousands of years, and despite medical advances that can now help us prevent and cure it, the ancient bacterial disease still claims more human lives per year than any other infectious pathogen.

In a new study, researchers unveil a device meant to demystify the early stages of TB, including a peculiar delay that often precedes the onset of symptoms.

Their model could also reveal how genetic variations in patients lead to varying effects of TB, with potentially broad implications for personalized medicine.

About a quarter of our species is infected with TB bacteria, and while only a fraction of those people will become sick, that still amounts to more than 10 million new cases – and more than 1 million deaths – per year worldwide.

TB progresses slowly, with symptoms often taking months to appear. To learn more about this lag, the authors focused on tiny air sacs in the lungs, pulmonary alveoli, which host pivotal confrontations between immune cells and bacteria.

"The air sacs in the lungs are a critical first barrier against infections in humans, but we've traditionally looked at them in animals like mice," says co-author Max Gutierrez, who leads the Host-Pathogen Interactions in Tuberculosis Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute.

"These studies are fundamental for our understanding, but animals and humans have differences in the makeup of immune cells and disease progression, sparking interest in alternative technologies," Gutierrez says.

Emerging "organ-on-a-chip" technology, for instance, lets scientists simulate a full human organ within a microfluidic cell culture microchip, offering an alternative to animal models.

Some "lung-on-a-chip" systems already exist, but limitations of those models inspired Gutierrez and his colleagues to try a different approach.

"Until now, lung-on-chip devices have been made of a mixture of patient-derived and commercially available cells," Gutierrez says. "This means that they can't fully recreate the lung function or disease progression of a single individual, as each type of cell is genetically different."

The researchers instead developed a new lung-on-a-chip for their study, featuring only genetically identical cells derived from a single human stem cell.

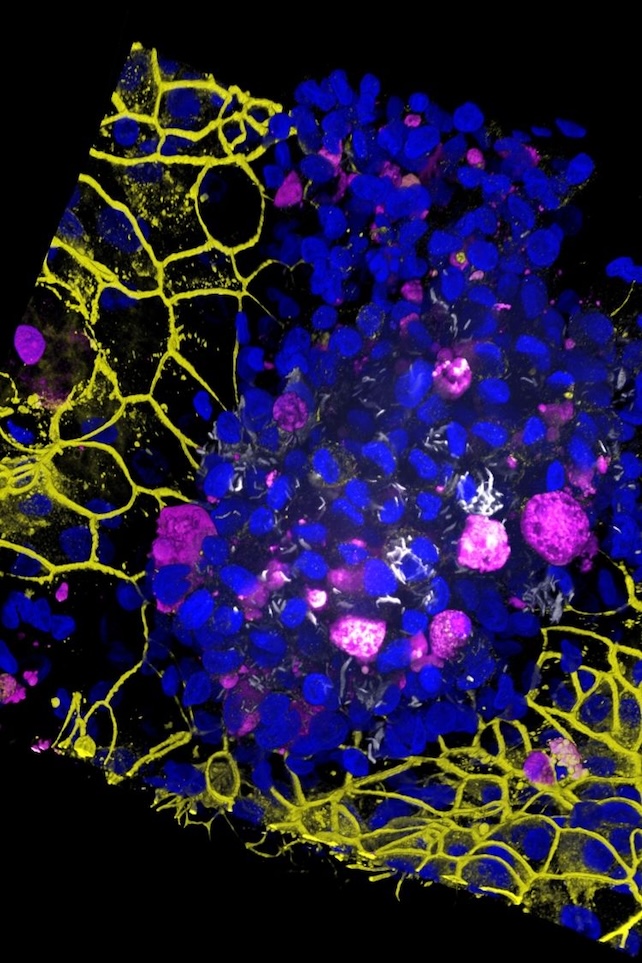

"We used human induced pluripotent stem cells, which can virtually become any cell in the body, to produce type I and II alveolar epithelial cells," says first author Jakson Luk, a postdoctoral fellow in Gutierrez's lab.

"These are grown on the top of the membrane," he adds. "Using the same stem cells, we also produced vascular endothelial cells that are grown on the bottom of the membrane."

This offered a novel look at the 'black box' period of TB, or the time between a person's initial infection and the onset of symptoms.

"We wanted to look for hallmarks of disease that have been reported in patients from the clinic and animal studies," Luk says.

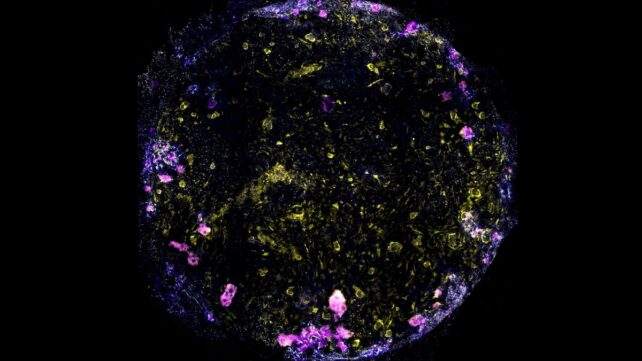

When researchers added immune cells called macrophages to the chip before introducing TB, they soon noticed macrophage clusters with "necrotic cores" – a central group of dead macrophages nestled in a larger group of live ones.

"Eventually, five days after infection, the endothelial and epithelial cell barriers collapsed, showing that the air sac function had broken down," Luk says.

Not everyone's lungs react to TB the same way, however, so the researchers also sought to learn how genetic differences can lead to varying responses.

"We removed the ATG14 gene, which is involved in a natural process for degrading damaged cells and foreign materials," Luk says.

"Macrophages lacking this gene were more susceptible to cell death in resting conditions, and tried to engulf more TB bacteria when infected, confirming the gene's role in keeping our immune defenses intact," he explains.

More research will be needed, but Luk and his colleagues see their chip as a key step toward more personalized treatment of TB – and other infections, too.

"We could now build chips from people with particular genetic mutations to understand how infections like TB will impact them and test the effectiveness of treatments like antibiotics," Luk says.

"The chip supports the big push into personalized medicine," Gutierrez adds. "It could help us understand the impact of genetics on whether a treatment is effective or not."

The study was published in Science Advances.