Scientists and philosophers alike have long pondered how time can appear to evaporate in a flash or drag out interminably, depending on the event.

A new study has pinpointed one part of the brain where that perception happens – in rodents, at least.

In tests on rats, researchers from the University of Oxford and University College London in the UK, as well as the Champalimaud Foundation in Portugal, found slowing down or speeding up activity in this brain region changed how the animals were able to judge time.

The experiments were focussed on a deep section of the brain called the striatum, which is linked to motor and action planning, and making decisions. Small changes in temperature were used to tweak the striatum's neural activity.

"Temperature has been used in previous studies to manipulate the temporal dynamics of behaviors, such as bird song. Cooling a specific brain region slows down the song, while warming speeds it up, without altering its structure," says behavioral ecologist Tiago Monteiro from the University of Oxford.

"We thought temperature could be ideal as it would potentially allow us to change the speed of neural dynamics without disrupting its pattern."

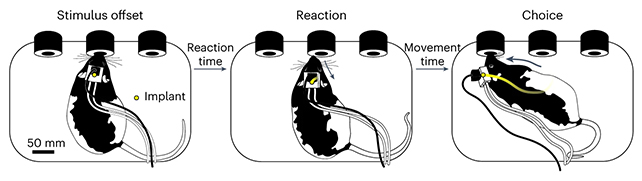

The researchers used implants to warm or cool the brains of the rats. Analysis under anesthesia showed striatum brain activity speeding up as the temperature rose, and slowing down as the temperature dropped.

When the rats were conscious, these same changes in temperature and brain activity mapped to altered perceptions of time in lab experiments. A warmer, faster striatum meant time passed less quickly; a cooler, slower one meant time passed more quickly.

However, the temperature changes (and subsequent brain pattern changes) didn't affect the speed that the rats moved at – only the speed that they decided to initiate movements. It seems that perceiving how quickly time passes, and how quickly movement should be made, are handled by two different parts of the brain.

In other words, the striatum handles when to swing a tennis racket, while another brain area handles the speed of the actual swing. That other area could be the cerebellum, the researchers say, a region associated with motor control and coordination.

Previous MRI data has suggested the basal ganglia is also involved in timing behavior in humans, but a lot more research will be needed to see how exactly this translates across species.

We use time all the time, and when our sense of it is impaired – as with Parkinson's for instance – movement and perception are affected. The study shines more light on the inner brain mechanisms involved in mammals.

"There's plenty more mystery to unravel," says Monteiro.

"What brain circuits create these timekeeping ripples of activity in the first place? What computations, other than keeping time, might such ripples perform? How do they help us adapt and respond intelligently to our environment?"

The research has been published in Nature Neuroscience.