It's sometimes said that you can smell fear, when, in fact, the signals that generate fear are often multi-sensory.

A fire, for instance, has heat, smoke, and smell to give it away. An eagle flying overhead casts a shadow and creates a flapping sound as it swoops.

It would be helpful for survival if animals had a way to feed all that sensory information from sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing into one neural circuit that triggered a part of the brain called the amygdala to initiate a fear response once a certain threshold was reached.

Yet the existence of such a neural pathway has yet to be established. A new study has now provided strong evidence of two, non-overlapping circuits that work together to strike fear into our brains.

The team of researchers behind the study started with suspicions that neurons that make use of a molecule called calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) played a strong role in the process, along with the brain's 'fear center' – the amygdala.

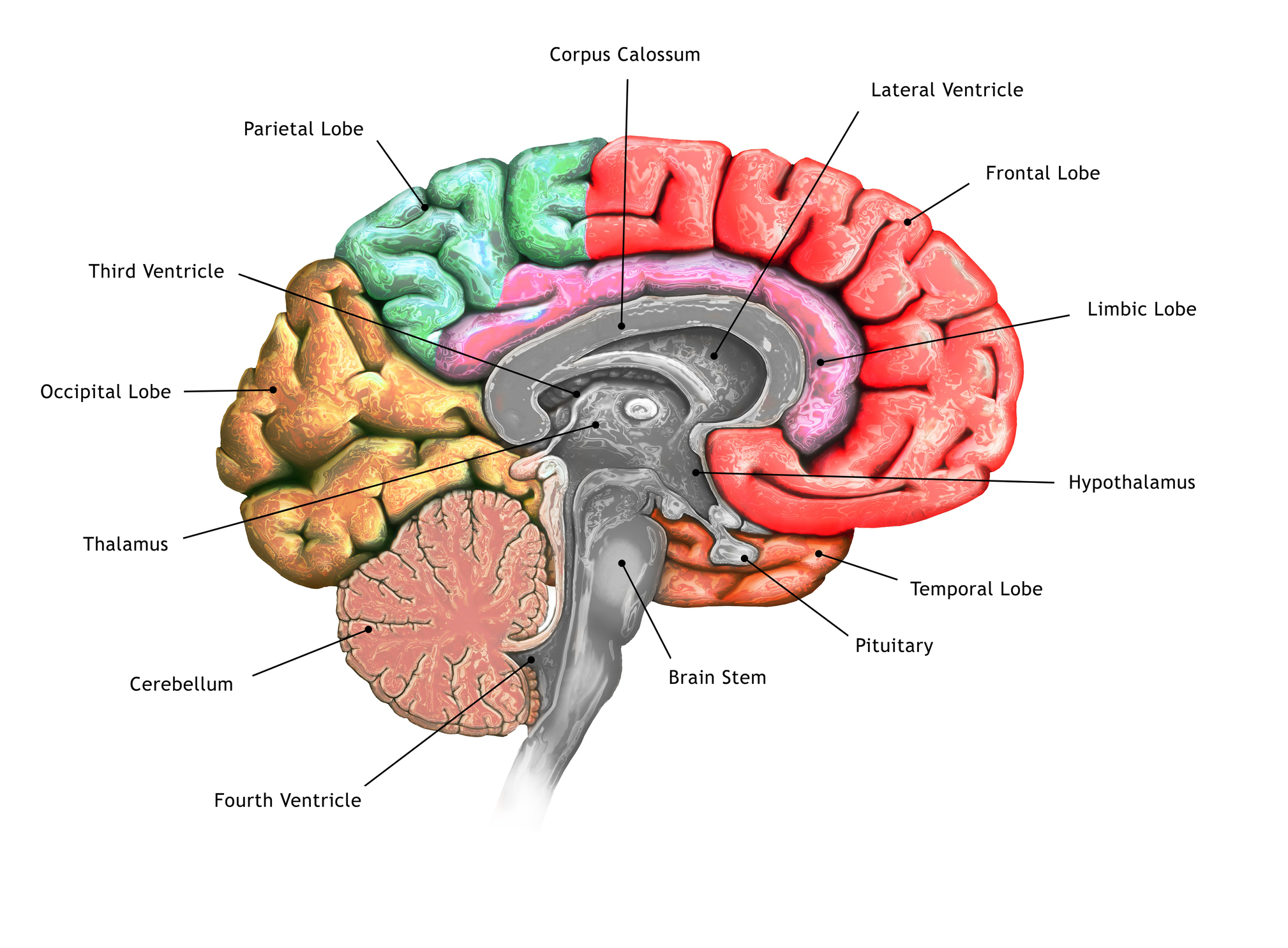

Testing their hypothesis on genetically modified mice, they found two distinct populations of these CGRP neurons in the brainstem and thalamus that connected into the animal's amygdala.

Human neurons also express CGRP so it's possible that this circuit could be involved in conditions such as migraines, PTSD, and autism spectrum disorder.

The researchers fitted mice with a small device for calcium imaging called a miniscope, which allows scientists to track the activity of the CGRP neurons while the mouse is freely roaming and responding to its environment.

Mice were then confronted with threat stimuli, including a small shock to their foot; a burst of sound mimicking a thunder blast; an expanding, looming disk simulating the rapid approach of a bird overhead; a cotton top soaked in trimethylthiazoline, a component of fox feces that sparks fear in rodents; and quinine solution, which tastes bitter.

The scientists recorded the activity of 160 CGRP neurons, half of each of the two varieties: CGRPSPFp and CGRPPBel.

They found that most CGRP neurons increased their activity when the mouse was confronted with threatening sounds, tastes, smells, sensations, and visual cues. The neurons did not respond as strongly to control stimuli.

"The brain pathway we discovered works like a central alarm system," says Sung Han, a neurobiologist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California.

"We were excited to find that the CGRP neurons are activated by negative sensory cues from all five senses – sight, sound, taste, smell and touch."

The researchers wanted to confirm that these CGRP neurons were required for multi-sensory threat perception. In other words, that other neurons were not triggering the same fear response.

In mice they silenced the CGRP neurons and ran the experiment again to see if the animals continued to show the same pattern of fear behavior in response to scary stimuli.

Mice that had these neurons silenced were significantly less likely to respond to an electric foot shock or loud sounds, the researchers found.

"These results indicate that CGRPSPFp and CGRPPBel neurons are required for mediating behavioral responses to different sets of multi-sensory threats," the researchers write in their paper.

The team also demonstrated that these CGRP neurons were necessary for forming memories of threats using a so-called Pavlovian learning experiment.

By converging all these threat signals into a single area of the brain, it may help animals facilitate decision-making, the researchers conclude.

If this same CGRP neural circuit is found in humans, then this research may inform treatments for medical conditions.

"We haven't tested it yet, but migraines might also activate these CGRP neurons in the thalamus and brainstem," says neuroscientist and co-first author Sukjae Joshua Kang, also of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

"Drugs that block CGRP have been used to treat migraines, so I'm hoping that our study can be an anchor to use this kind of drug in relieving threat memories in PTSD, or sensory hypersensitivity in autism, too."

This paper was published in Cell Reports.