Most of us know the feeling of being unable to distract ourselves from a particular thought, however much we might want to. Now, scientists might have found the reason why.

In a study carried out at the University of Cambridge, participants were given pairs of words to associate with one another. The words were unrelated in order to ensure that pre-existing associations didn't have any influence.

Participants were then given a word and either a green or a red signal. If it was the former, they would try to recall the other half of the pairing, and if it was the latter, they would try to deliberately suppress the associated term from their mind.

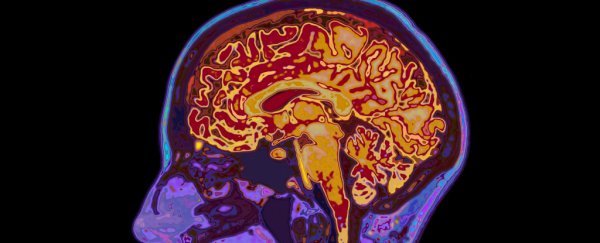

While this test was being carried out, participants' brains were monitored using functional magnetic resonance imaging, a technique that monitors changes in blood flow, as well as magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which tracks chemical changes.

Participants with the highest concentrations of a chemical known as GABA in their hippocampus were best at suppressing the unwanted thoughts. GABA is the brain's primary inhibiting neurotransmitter, stifling the activities of other cells when it's released.

"What's exciting about this is that now we're getting very specific," said Michael Anderson, who led the study, in an interview with the BBC.

"Before, we could only say 'this part of the brain acts on that part', but now we can say which neurotransmitters are likely to be important."

A difficulty with or an inability to break free from intrusive and unwanted thoughts are a reality both for neurotypical people and also for those with various types of mental illness.

Conditions ranging from obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder to depression and schizophrenia all count this type of behavior among their symptoms.

As such, there are hopes that these findings could offer further insight into the chemical basis of these disorders. At present, much of the research into treatment methods has centered around helping the prefrontal cortex to function normally.

However, Anderson believes that figuring out a way to promote GABA activity in the hippocampus could actually offer more positive results.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.