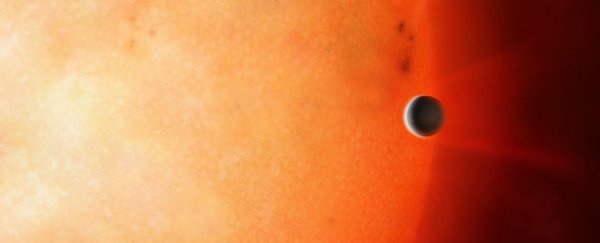

If you've always wanted to discover a planet for your very own, now's your chance. Researchers are calling on the public for help in identifying exoplanets – planets orbiting stars outside of our own Solar System.

The Planet Hunters Next-Generation Transit Search (NGTS), run by an international group of astronomers, has five years' worth of digital footage that needs sifting through. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to spot stars that briefly dim, perhaps suggesting a planet is passing in front of them.

That's known as a transit by the experts, but you don't need any experience to get involved in trying to spot one. All you need is a keen eye and some patience to sift through the images collected by the NGTS telescopes based at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) Paranal Observatory in Chile.

"It is exciting to be able to involve the public in our search for planets around other stars," says astrophysicist Peter Wheatley from the University of Warwick in the UK and the lead of NGTS. "We are pretty sure our computer programs are missing some planets."

"These will be the most unusual signals and so probably some of the most interesting planets. Humans are still smarter than machines, and I can't wait to see what our volunteers unearth."

There's plenty of data to get through: Every 10 seconds, the NGTS telescopes capture shots of thousands of stars in the sky. Algorithms are used to flag up possible transit events, but these algorithms aren't perfect.

The software can pick out dimmings that aren't exoplanets, as well as miss dimmings that are – and that's where people come in. If you decide to get involved, you'll be shown charts of light readings taken of stars out in space, known as 'folded' light curves, or the measurement of a star's brightness as it changes over time combined with the software's read of a planet's potential orbit.

Your job will be to categorize these charts and identify the shapes that they show, with volunteers and experts cross-checking each finding to try and help identify exoplanets that have otherwise been missed.

One of the folded light curves you'll have to identify. (NGTS)

One of the folded light curves you'll have to identify. (NGTS)

"The automated algorithms produce lots and lots of possible candidate transit events that need to be reviewed by the NGTS team to confirm whether they are real or not," says astronomer Meg Schwamb, from Queen's University Belfast in the UK.

"Most of the things spotted by the computers are not due to exoplanets, but a small handful of these candidates are new bona fide planet discoveries."

Head over to the Planet Hunters NGST page to get started. There's no application process or fee – all you need is a web browser and a passion for making scientific discoveries. Thousands of volunteers have already got involved, but there's still a lot of work to do.

These kinds of citizen science discoveries are more common than you might think. From the Australian mechanic who spotted an unusual four-planet solar system, to the amateur metal detectorist from Britain who came across a huge cache of ancient Roman treasures.

Plenty of help is available if you get stuck, and who knows – you might end up making a vital contribution in the hunt for planets outside of our neighborhood.