The way information travels inside the cells of our bodies is not unlike the wiring inside a computer chip, according to a new study that has unveiled the intricate workings of a network of calcium ions as intracellular messengers.

According to researchers from the University of Edinburgh in the UK, this "cell-wide web" uses a microscopic network of guides to transmit information across nanoscale distances and carry activities and instructions for the cells to perform - such as relaxing or contracting muscles, for example.

Calcium ions (Ca2+) are a fundamental part of the messaging system of our cells, and their signals are crucial for a wide variety of jobs, including cell growth, death, and movement. Now researchers have taken an unprecedented close look at just how calcium ions shuttle messages within the cell.

Animal cells, as you may remember from textbooks, look a bit like sacks with various structures called organelles floating within, suspended in a gel-like substance known as cytosol.

All together, these internal cell contents make up cytoplasm; up until now, it was thought that calcium ions pulse through the cytoplasm to tell the cells what to do. But now it appears their communications are more structured than that.

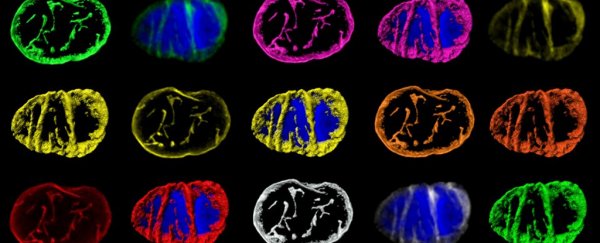

Nanocourses inside a cell. (University of Edinburgh)

Nanocourses inside a cell. (University of Edinburgh)

The researchers discovered that calcium ions have their own network of 'wiring': these are called nanocourses, and they travel all the way to the nucleus at the heart of the cell and control which genes are then released and expressed.

The wiring is not static, either; as cell behaviour changes, these nanocourses can be reconfigured accordingly.

"The most striking thing is that this circuit is highly flexible, as this cell-wide web can rapidly reconfigure to deliver different outputs in a manner determined by the information received by and relayed from the nucleus," says one of the researchers, cellular pharmacologist Mark Evans.

The team used rat cells to closely investigate this phenomenon, and used electron microscopy to uncover precisely how these nanocourses work.

The researchers explain that the series of calcium ion-carrying nanocourses work somewhat similarly to how carbon nanotubes are used in a computer microprocessor - although cells seem to be more advanced than that.

"Critically, this circuit is not hardwired and remodels for different outputs during cell proliferation," explain the researchers in their published paper.

"This is something no man-made microprocessors or circuit boards are yet capable of achieving," adds Evans.

According to the team, knowing more about how cells handle instructions could help inform the treatment of all kinds of health issues, including pulmonary hypertension or even the growth of cancer.

The next step is understanding exactly how calcium ions work as code in programming cells to express different genes; then, perhaps we could start to tap into this process down the line.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.