In the water, it's getting harder to breathe. Suffocating dead zones with little or no oxygen are pervading the world's oceans, rivers, and streams.

This phenomenon – which has exploded in recent decades – poses an extinction-level nightmare for marine populations already beset by a complex interaction of human-made menace.

When it comes to these oxygen shortages, however, some fish might not be too bothered.

In a new paper, researchers report the discovery of deep-sea fish who were found thriving in virtually oxygen-less conditions that scientists previously assumed to be deadly.

"I could hardly believe my eyes," biological oceanographer Natalya Gallo from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography explains in a blog detailing the research.

"We observed cusk-eels, grenadiers, and lollipop sharks actively swimming around in areas where the oxygen concentration was less than one percent of typical surface oxygen concentrations."

(MBARI)

(MBARI)

In 2015, Gallo and fellow researchers conducted eight dives with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) on an expedition in the Gulf of California led by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI).

Readings from sensors on the ROV indicated the oxygen concentrations in this environment were between one-tenth to one-fortieth as low as those tolerated by other low-oxygen-tolerant fish.

"We were in a suboxic habitat, which should exclude fish, but instead there were hundreds of fish," Gallo explains.

"I immediately knew this was something special that challenged our existing understanding of the limits of hypoxia [low-oxygen] tolerance."

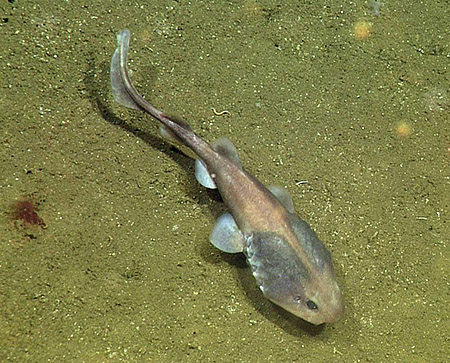

A lollipop shark (Cephalurus cephalus) (MBARI)

A lollipop shark (Cephalurus cephalus) (MBARI)

According to the researchers, fish are generally considered hypoxia intolerant due to their metabolic requirements, but clearly some extremophiles swim within their scaly ranks.

Even amongst such exceptional fish, though, the cusk-eel (Cherublemma emmelas) and the lollipop catshark (Cephalurus cephalus) look to be outliers, peaking in number at depths of between 600–900 metres (1,969–2,953 ft).

Alongside these, the researchers also observed the occasional grenadier (Nezumia liolepis) and ogcocephalid anglerfish (Dibranchus spinosus), but in fewer numbers, and seemingly preferring to occupy more oxygenated waters.

"Prior to this study, fish were not expected to tolerate hypoxic conditions this severe," the authors explain in their paper, although they acknowledge they're not able to explain how C. emmelas and C. cephalus developed the ability to thrive under these extreme suboxic conditions.

It's hypothetically possible, the researchers suggest, that enlarged gills have enabled both species to ramp up their oxygen uptake.

They may also possess low metabolic requirements thanks to their small, soft bodies, but Gallo and her co-authors point out further in-depth examinations would be needed to verify this.

As the study acknowledges, other sorts of extremophiles have names to denote their special abilities; animals that tolerate high temperatures are called hyperthermophile, while creatures that can handle high levels of salt are known as halophile.

The extreme hypoxia tolerance of C. emmelas and C. cephalus is unprecedented, however, so the researchers say we need a new name for them. They propose 'ligooxyphile', which in Greek equates to 'little oxygen lover'.

However these amazing animals got this way, it's a unique trait other marine life might sadly be forced to emulate, and soon – or die trying.

The way things are headed, though, even extremophiles are up against it, the researchers warn.

"Continued warming of the ocean may challenge even the most hypoxia-tolerant fishes," says one of the team, Scripps biological oceanographer Lisa Levin.

"Elevated temperature will lower the solubility of oxygen in the water while increasing the amount of oxygen the fish need to survive."

The findings are reported in Ecology.