Neuroscientists in the US have identified parts of the brain responsible for accurate spelling, and say a better understanding of what goes on in our heads when we get it wrong could lead to new treatments and techniques to more effectively teach children and those with cognitive disabilities to read and write.

A team from Johns Hopkins University studied 15 years' worth of stroke cases, and identified 33 patients who had been left with impaired spelling capabilities as a result. The stroke victims varied in the type of problems they experienced: some had issues with long-term memory, while others had issues with their working memory.

Those with long-term memory problems typically couldn't remember how to spell words they once knew, and would make educated guesses - trying "soss" when they want to write "sauce", for example. On the other hand, those with working memory problems knew how words should be spelled, but had difficulty getting the letters in the right order.

By using computer mapping technology, the researchers were able to spot lesions in the brain that hampered the participants' spelling prowess.

"When something goes wrong with spelling, it's not one thing that always happens - different things can happen and they come from different breakdowns in the brain's machinery. Depending on what part breaks, you'll have different symptoms," said lead researcher, Brenda Rapp.

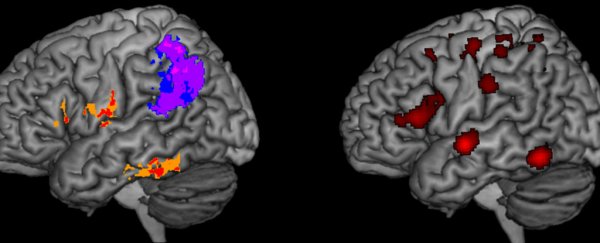

In the case of those with long-term memory loss, damage appeared in two areas of the left hemisphere of the brain: one towards the front, and one in the lower region towards the back.

For those with working memory loss, lesions were also found in the left hemisphere of the brain, but this time in the upper area around the back. It's the first time these seemingly unrelated regions of the brain have been linked with basic spelling difficulties.

"I was surprised to see how distant and distinct the brain regions are that support these two subcomponents of the writing process, especially two subcomponents that are so closely interrelated during spelling that some have argued that they shouldn't be thought of as separate functions," said Rapp. "You might have thought that they would be closer together and harder to tease apart."

It's early days yet, but the new data gathered by Rapp and her team might eventually help scientists work out improved methods for teaching spelling, whether to patients recovering from a stroke, or those enrolling in school for the first time. Spelling issues are of course associated with a host of other conditions as well, including dyslexia, and it could lead to advances in our understanding of these conditions too.

The group's work has been published in the journal Brain.