The history of Earth isn't written in ink, but in ancient ice - buried under places so unforgivingly frozen, they're usually mistaken for wastelands.

And if you extract deep, concealed cores of ice from within these extreme latitudes, you can learn almost anything: about metal workers vanquished by the Black Death, or the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, or even our planet's leaking oxygen supply.

Now, scientists say they have likely found an ice core that's unlike any of these frozen history lessons.

Until now, the oldest continuous core that we knew about is one that stretches back in time some 800,000 years from the present day in an unbroken flow of ice and trapped chemicals, which tell us things about the environmental and atmospheric conditions when the ice formed.

That 800,000-year-old core comes from a site called Dome C in Antarctica, but even though it's plenty old, scientists think we can go back even further.

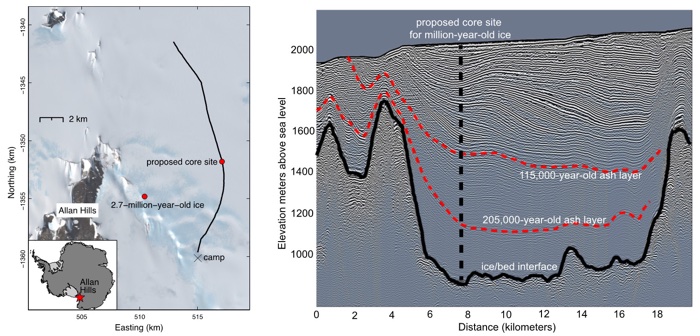

(Laura Kehrl/University of Washington)

(Laura Kehrl/University of Washington)

"There's a strong desire to push back the date of the oldest ice core record, to better understand what drives natural climate changes," says polar geologist Laura Kehrl from the University of Washington, who with fellow researchers has been investigating the icy depths under Antarctica's Allan Hills.

"The Allan Hills has been an area of interest since the 1970s, when scientists started finding lunar and Martian meteorites that had struck Earth long ago," says Kehrl.

"Now we're discovering its potential for old ice."

The Allan Hills fall within a region called the Transantarctic Mountains, whose steep, uneven topography was long thought to be too unstable to contain deep, ancient ice of this kind.

At least, it was until last year, when a separate study by researchers at Princeton University found an isolated fragment of ice a stunning 2.7 million years old under the Allan Hills.

Unfortunately, because that broken fragment was separated from the rest of its icy timeline, there's a limit to how much it can tell us about Earth's environmental conditions falling outside its own frozen spotlight.

(Laura Kehrl/University of Washington)

(Laura Kehrl/University of Washington)

But the discovery nonetheless showed that Allan Hills could yet be fertile territory for continuous ice columns standing a million years tall.

To investigate, Kehrl and her team set up a remote camp in the Allan Hills at 1,950 metres (6,400 feet) above sea level, and used snow machines to tow ice-penetrating radar over the frosty, bluish surface.

The radar signals bounce off layers of ice hidden under the surface, revealing differences in things like ice chemistry and density.

Using this technique – and computer modelling to simulate glacier flow in the area – the team says they've pinpointed the probable location of where million-year-old ice could be lurking under the Allan Hills, some 5 kilometres (3 miles) away from where the 2.7 million-year-old ice fragment was discovered.

The team has now applied to the National Science Foundation for permission to drill into their proposed core site, and if their submission is approved, we could be looking at an unprecedented, continuous core of unparalleled age and composition – and there's no telling just what we might learn.

"Regardless of whether the million-year ice is there," Kehrl says, "the record is likely to be valuable."

The findings are reported in Geophysical Research Letters.