A new contender for a human 'language gene' can change the way that mice squeak when it is incorporated into their DNA.

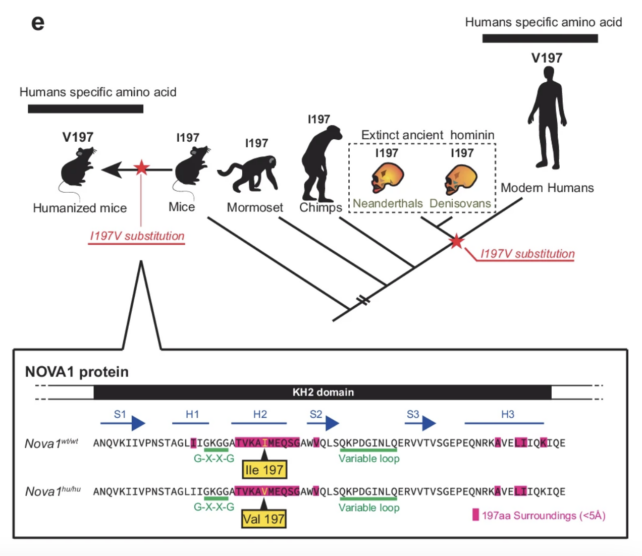

The gene is called NOVA1, and in our own species, it is remarkably unique. While virtually all other mammals have the same NOVA1 variant in their genetic code, a single change of an amino acid is seen in the human version.

This one, subtle tweak may have played a critical role in the origins of spoken language and the expansion and survival of Homo sapiens, according to researchers at Rockefeller University and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

Not even Neanderthals and Denisovans have the same variant, which means it must have evolved in the last few hundred thousand years, after our species split from these extinct relatives.

Other proposed 'language genes', like FOXP2, which also make mice squeak differently are found in the DNA of Neanderthals. So even though they probably also contributed to the origins of human language, they may not be responsible for our more recent evolutionary success.

It's not clear what the language capabilities of our extinct relatives once were, but this recent change has proved highly successful in the human genome.

In more than 650,000 human DNA sequences, researchers found only six anonymous people who did not have the modern NOVA1 variant. Nothing about these individuals is known.

When it comes to the origins of complex human language, NOVA1 is "the new kid on the block", geneticist Wolfgang Enard who worked on the FOXP2 gene told Carl Zimmer at The New York Times.

"This gene is part of a sweeping evolutionary change in early modern humans and hints at potential ancient origins of spoken language," says neuro-oncologist Robert Darnell from Rockefeller University, who has been studying the gene and its links to disease and intellectual function since the early 1990s.

"NOVA1 may be a bona fide human 'language gene,' though certainly it's only one of many human-specific genetic changes."

When Darnell and his team artificially generated the human variant of NOVA1 in mice, they found that the rodents squeaked differently. Adults and pups still made the same amount of noise, but their vocalization patterns had changed.

Compared to typical mice, genetically modified pups made higher-frequency ultrasonic squeaks. Their calls didn't get their mother's attention any more than the calls of a control pup, but these sounds may indicate an increased attempt at social interaction, albeit a failed one.

Higher frequency calls are also used by adult male mice during courtship for similar reasons. When adult male mice were genetically altered with the human NOVA1 variant, their squeaks during courtship didn't become higher pitched like the pups. Instead, their vocalizations included more complex syllables.

"They 'talked' differently to the female mice," explains Darnell. "One can imagine how such changes in vocalization could have a profound impact on evolution."

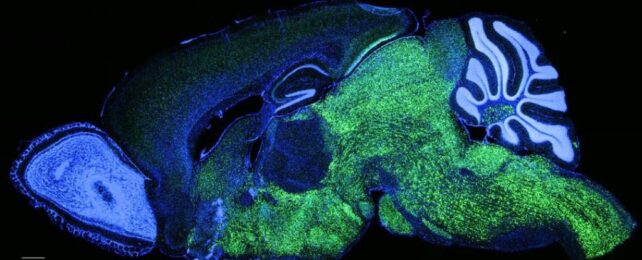

Why the mice sound different with the human NOVA1 variant is a mystery that Darnell and his colleagues are keen to solve. The team suspects that the human variant is causing molecular shifts in some parts of the developing rodent brain – whether it be the vocal pathways of the midbrain and brainstem or more recently evolved regions in the cortex, which control pitch and frequency.

The NOVA1 gene is known as a 'master gene regulator' because it influences more than 90 percent of other human genes during development.

NOVA1 encodes a protein called Nova-1 that can cut out and rearrange sections of messenger RNA when it binds to neurons. This changes how brain cells synthesize proteins, probably creating molecular diversity in the central nervous system.

When Darnell and his team 'humanized' mice with the NOVA1 variant, they found molecular changes in the RNA splicing seen in brain cells, especially in regions associated with vocal behavior.

"We thought, wow. We did not expect that," Darnell says. "It was one of those really surprising moments in science."

For Darnell, understanding NOVA1 has been a career-long effort.

NOVA1 is thought to help regulate learning in humans, and mutations in this gene can cause severe psychiatric disorders and abnormalities in motor development.

Its role in speech development is just starting to emerge, and while much remains hypothetical, the possibilities are profound.

"Our data show that an ancestral population of modern humans in Africa evolved the human variant I197V, which then became dominant, perhaps because it conferred advantages related to vocal communication," suggests Darnell.

"This population then left Africa and spread across the world."

No doubt having a chat on the way.

The study was published in Nature Communications.