There's more than 32 times as much energy in a magnitude 8 earthquake as there is in a magnitude 7 earthquake – and scientists have discovered a natural 'gate' that controls which quakes are allowed to increase up to that highest scale.

The gate in question is at the Alpine Fault in New Zealand. A new analysis estimates that the fault has around a 75 percent chance of producing a damaging earthquake within the next 50 years or so.

That's partly down to the earthquake gate that the research team has identified: a particular set of geological conditions that can stop a quake from growing. At the Alpine Fault, the next major earthquake has an 82 percent chance of passing through the gate and reaching a magnitude 8.

"An earthquake gate is like someone directing traffic at a one-lane construction zone," says geologist Nicolas Barth, from the University of California, Riverside. "Sometimes you pull up and get a green go sign, other times you have a red stop sign until conditions change."

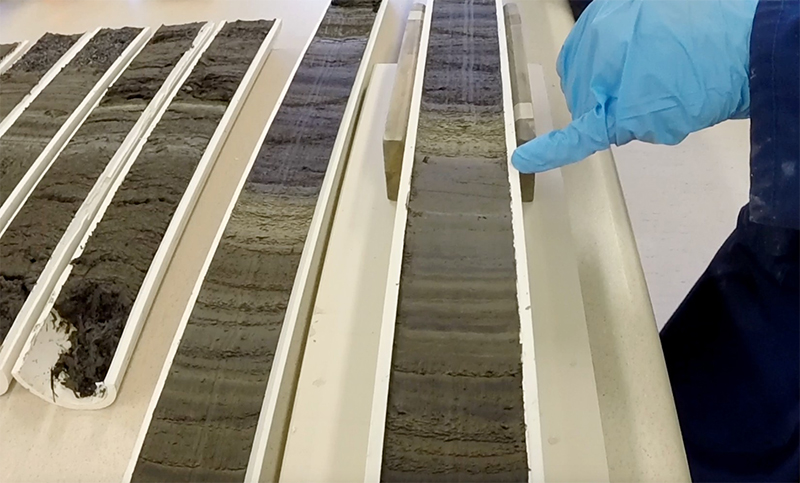

Barth and his colleagues combined computer models with sedimentary records collected from six different sites. The sediments – which trap evidence of ground shakes and landslides – showed the extent of 20 major earthquakes along the Alpine Fault over the last 4,000 years.

The modeling was then able to show how fault geometry like steps and bends in the rock could block off certain types of quake – but every earthquake affects the state of the fault and the gate, and makes conditions different for the next time.

"The simulations show that a smaller magnitude 6 to 7 earthquake at the earthquake gate can change the stress and break the streak of larger earthquakes," says Barth.

"We know the last three ruptures passed through the earthquake gate. In our best-fit model the next earthquake will also pass 82 percent of the time."

Alpine Fault sediment record. (Jamie Howarth/Victoria University of Wellington)

Alpine Fault sediment record. (Jamie Howarth/Victoria University of Wellington)

Other earthquake gates around the world are also under investigation, but the 4,000 years of sediment data and 100,000 years of AI-generated simulations at New Zealand's Alpine Fault give geologists a particularly large pool of data to study.

Another area currently being studied is at the Cajon Pass in the US, where the combination of the San Andreas and San Jacinto faults could cause gate-like behavior that would affect the size of future earthquakes.

As more earthquake gates are identified and understood, predictions and models can improve – not only in terms of why and when earthquakes happen, but the sort of hit it might make on the magnitude scale.

"We are starting to get to the point where our data and models are detailed enough that we can begin forecasting earthquake patterns," says Barth. "Not just how likely an earthquake is, but how big and how widespread it may be, which will help us better prepare."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.