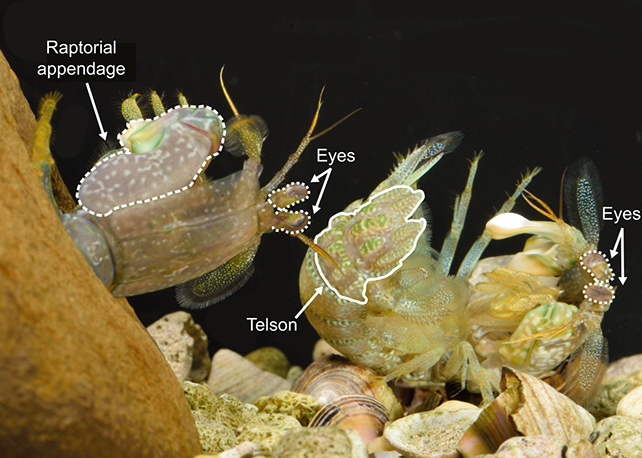

Mantis shrimp are fascinating creatures, equipped with the fastest punch in all the oceans – a knock-out move with an acceleration similar to a 22-caliber bullet. New research helps explain how the shrimp help protect themselves from those stunning blows when fighting each other.

Previous studies have looked at how the telson (armored tail plate) of a mantis shrimp can dissipate 69 percent of the energy of an opponent shrimp's punch. However, those measurements were taken in lab conditions with the telsons laid flat.

Here, ecologist Patrick Green, from the University of California, Santa Barbara, used high-speed cameras capable of capturing up to 40,000 frames per second to record the creatures in their normal fighting stance.

"In natural fights, we see mantis shrimp coil their tails in front of their bodies like a shield," says Green, who dubbed the behavior 'telson sparring' when he started studying shrimp fights years ago.

In this new study, Green says he "wanted to know how this behavioral use of the tail changed how they receive impacts."

Analyzing the movement of the shrimps' appendages before and after impact allowed Green to calculate how much energy an aggressor imparted and the defender dissipated from each strike.

Green found that coiling their tail enhanced the overall strength of the shrimp's body considerably. In fact, an additional 20 percent of a punch's force can be absorbed because of how mantis shrimp position themselves when there are conflicts.

"It made logical sense to me that holding your armor off the ground should let you dissipate more energy," says Green. "Think about a boxer moving with a punch that they receive."

There's likely more to discover here, according to Green. More than 400 species of mantis shrimp are known to exist across the world, with each one having their own variations in terms of telson tail plates, and fighting frequencies.

These little creatures, who grow to around 10 centimeters (3.9 inches) in length, continue to intrigue scientists. As well as being super-tough, they can also see different spectrums of light, thanks to their special visual sensing system – which is actually able to spot cancer before symptoms show up.

Fights usually break out between these crustaceans over territory, and it's thought that these sparring matches may be a way of assessing the strength of a rival – so that the animals know when they might be taking on too big a challenge.

Future work could look at this punching and blocking behavior in a more three-dimensional way, Green suggests, looking in detail at how the angle of attack and defense affects the amount of energy that can be dissipated.

Ultimately though, this latest study shows the importance of considering both the defensive armor that's in place, as well as how that armor is used, when studying how animals handle powerful impacts.

"This study helps us connect behavior and morphology, so we can better understand how animals navigate their fights," says Green.

The research has been published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.