Once gleaming with futuristic ambition, microwave ovens are often taken for granted in our modern kitchens and offices. But a spotlight shines upon these atomic-age appliances once again in a study involving our contemporary fascination with microbiomes.

A team of scientists from the University of Valencia and Darwin Bioprospecting Excellence SL in Spain has profiled the ecosystems living in our microwaves, and they've found some pretty extreme things going on in there.

Cleaning the inside of the microwave is something few people manage with daily regularity, save for when food gurgles out of its container. It's easy to assume the blast of microwaves is enough to sterilize whatever nasty life forms may be lurking in there, after all.

That might be the case for some microbes, but according to the study, it turns out that many microscopic organisms aren't phased by the intense electromagnetic radiation at all.

To isolate potential samples of microorganisms, the team swabbed the inner walls of 30 different microwaves: 10 from single household kitchens, 10 from shared domestic spaces (like the company break room, or a university cafeteria), and 10 from molecular biology and microbiology laboratories that are used specifically for experiments.

Brachybacterium, Micrococcus, Paracoccus, and Priestia showed up in microwaves from all locations. These genera – and many others isolated from the swabs – are associated with humans, living in and around us, benefiting from our existence while we barely acknowledge theirs.

Kitchen microwaves, unsurprisingly, had very similar microbial profiles to other kitchen surfaces, and our food. Some species, including Klebsiella, Enterococcus, and Aeromonas, can pose health risks, but their presence and abundance in domestic microwaves weren't any more concerning than on other common kitchen surfaces.

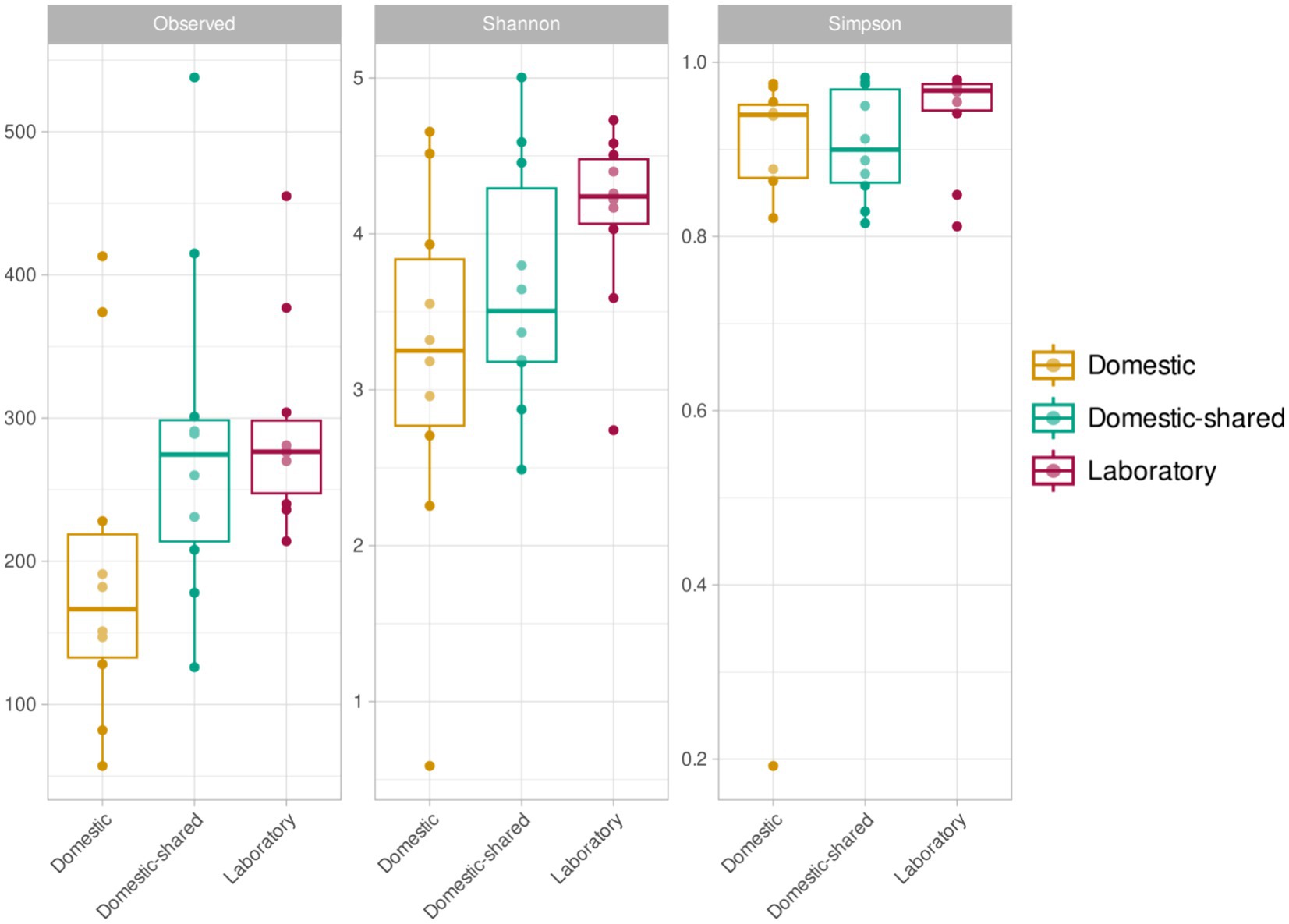

Single household microwaves had the lowest biodiversity lurking within, all scoring below four on a measure of proportional abundance called the Shannon diversity index. This makes sense given they likely have a lower variety of contamination sources than microwaves in shared spaces. A similar pattern contributes to the microbial diversity found within other appliances, like washing machines.

Laboratory microwaves were the most biodiverse of the three groups, with Shannon indices above four.

They didn't harbor the kitchen-style germs seen in their domestic counterparts, probably because they are used to heat aqueous solutions, biological samples, synthetic materials, or chemical reagents, rather than food.

The researchers suspected the primary factor determining laboratory microwave microbiomes would, therefore, be the extreme conditions created within them, since the heating processes they are used for often require longer exposure times.

"In fact, some of the genera that were significantly more abundant in this group of samples included species known for their resistance to high doses of radiation, such as Deinococcus, Hymenobacter, Kineococcus, Sphingomonas, and Cellulomonas," the team reports.

This microscopic community has much in common with those isolated from solar panels. And though the team also compared their samples with those taken from nuclear waste, thankfully, microwave microbes bore little similarity.

While the microbes found in domestic microwaves weren't quite so hardcore, the research shows how bacteria with the genetic potential to resist radiation, thermal shock, and desiccation can make themselves quite comfortable in spite of it all.

Given that even our friendly skin bugs seem to survive the oven's torrid waves, it's best to give your microwave a regular thorough clean with detergent, and stay on top of those spills.

This research was published in Frontiers in Microbiology.