Antarctica was once a lush and thriving land, teeming with prehistoric life. It's hard to believe now, but tucked away, hidden underneath a layer of ice kilometers thick, that ancient landscape still lies buried, never seen by human eyes.

Never seen, perhaps, but that doesn't mean forever to remain unknown. For years, the British Antarctic Survey has been flying planes over the frozen southern continent, using radar, sound waves, and gravity mapping to ascertain the shape of the bedrock sequestered below.

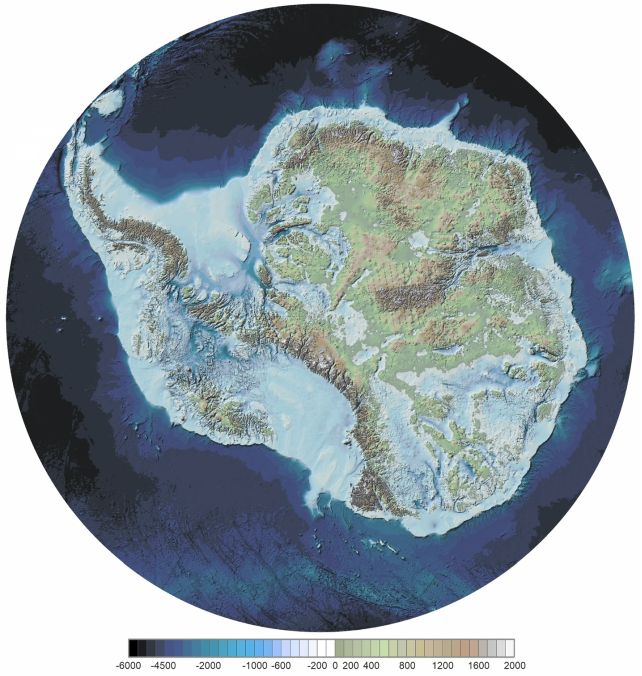

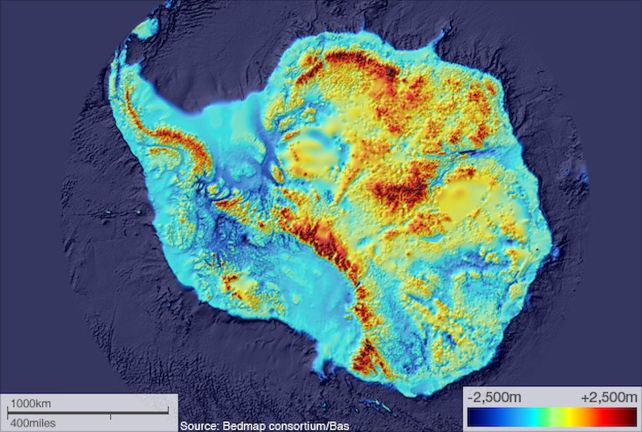

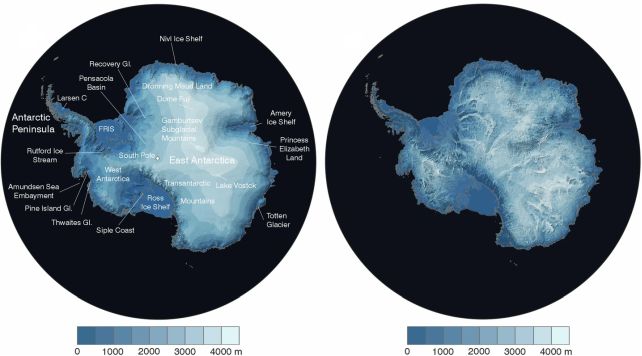

Their new map of Antarctica as it lies under the ice is the most detailed yet – revealing mountain ranges, ancient riverbeds, deep basins, and low, sweeping plains.

This, according to a team led by glaciologist Hamish Pritchard of the British Antarctic Survey, will provide crucial information to scientists looking to understand the complex interplay between land and ice as Antarctica continues to transform under a changing climate.

"This is the fundamental information that underpins the computer models we use to investigate how the ice will flow across the continent as temperatures rise," Pritchard says.

"Imagine pouring syrup over a rock cake – all the lumps, all the bumps, will determine where the syrup goes and how fast. And so it is with Antarctica: some ridges will hold up the flowing ice; the hollows and smooth bits are where that ice could accelerate."

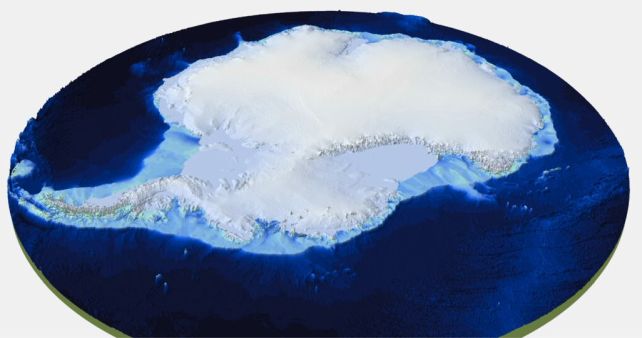

It's a fascinating question, really. If you removed the 27 million cubic kilometers (6.5 million cubic miles) of ice that covers Antarctica, what would the continent look like? What ancient geology is hidden thereunder; what history remains undiscovered?

It wasn't so long ago that we'd have little way of finding out. Now, we can fly planes and satellites carrying the sensitive tools of metrology to measure what we can't see. This is the work the British Antarctic Survey has been carrying out, incrementally adding more data over the course of six decades to fill in their map of what lies beneath.

The latest map, known as Bedmap3, comprises data collected from planes, satellites, ships, and dog sled teams on the ground to catalog the hidden landscape of Antarctica. The 277 ice thickness surveys used to compile the map contributed 82 million data points, filling in huge gaps in the previous map.

One of those gaps is the point at which the ice that covers Antarctica is at its thickest. Previous surveys had placed it in Adélie Land's Astrolabe Basin.

The new map, however, reveals that the true position is at 76.052 degrees South, 118.378 degrees East, where an unnamed canyon produces an ice thickness of 4,757 meters (15,607 feet).

Ice thickness surveys were particularly lacking around mountains, coastlines, and nunataks (isolated mountains sticking out of the ice). Bedmap3 clarified the regions around the South Pole itself, along the coastlines of the Antarctic Peninsula and West Antarctica, and the Transantarctic Mountains.

We know how high the top of the ice that covers Antarctica reaches from sea level. Mapping the topography of a mass that is open to the sky is relatively straightforward. By forging a more accurate map of the shape of the bottom of the ice, Pritchard and his colleagues could more accurately calculate how much ice is there.

The total volume of ice is 27.17 million cubic kilometers, covering an area of 13.63 square kilometers. The mean thickness of the ice, including the ice shelves, is 1,948 meters; excluding the ice shelves, it's 2,148 meters.

If all the ice in Antarctica was to melt, this means sea levels would rise by 58 meters. That's consistent with previous surveys, but with a couple of tweaks.

"In general, it's become clear the Antarctic Ice Sheet is thicker than we originally realised and has a larger volume of ice that is grounded on a rock bed sitting below sea-level," explains cartographer Peter Fretwell of the British Antarctic Survey.

"This puts the ice at greater risk of melting due to the incursion of warm ocean water that's occurring at the fringes of the continent. What Bedmap3 is showing us is that we have got a slightly more vulnerable Antarctica than we previously thought."

But hey, at least we might finally be able to find the Mountains of Madness…?

The team's research has been published in Scientific Data.