Scientists have developed a new way of treating cancer with iron nanoparticles, which were able to kickstart the immune system into attacking tumours in groups of mice.

In the study, macrophages (white blood cells) fought back against spreading tumours after a dose of iron nanoparticles, stopping the cancer from taking hold.

In addition to shrinking existing tumours in mice, the treatment stopped cancer tumours from spreading through the body, according to researchers from Stanford University and Oregon Health & Science University.

"It was really surprising to us that the nanoparticles activated macrophages so that they started to attack cancer cells in mice," said researcher Heike Daldrup-Link from Stanford. "We think this concept should hold in human patients, too."

The researchers used ferumoxytol for their tests, an iron supplement already available commercially for the treatment of anaemia, where the body doesn't have enough iron naturally.

Originally the idea was to use the iron nanoparticles as a kind of Trojan horse, sneaking chemotherapy into tumours. As it turned out, though, the control group of mice – which were given iron without chemo drugs – showed the best results in terms of tumour suppression.

Follow-up tests conducted in cells in a dish determined that it was the macrophages that were battling the cancer after receiving the iron – ordinarily, these macrophages stop attacking tumours and start helping their growth, once the tumours reach a certain size.

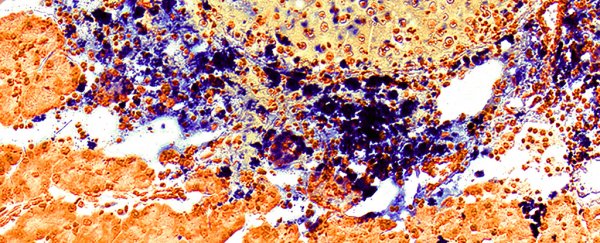

Credit: Amy Thomas/Stanford University School of Medicine

Credit: Amy Thomas/Stanford University School of Medicine

The researchers think the iron and macrophages were able to somehow restart cell apoptosis (natural programmed cell death) inside tumours. While the treatment isn't strong enough to remove cancer on its own, it could be if used in combination with existing drugs.

The dose of ferumoxytol used in the tests was similar to a safe dose given in the treatment of anaemia, with the anti-cancer effect from each dose seeming to last for around three weeks.

In subsequent tests, the team noticed iron nanoparticles having a suppressive effect on cancer metastasis – where tumours spread to nearby tissues and organs – and found the treatment reduced tumour size when given before the cancers were introduced.

Now the researchers want to work out ways in which this could benefit humans as a complement to existing chemotherapy.

While the results have only been seen so far in mice, the team hopes the iron nanoparticles might be able help while patients recover between doses of chemo – or perhaps clean up remaining tumour cells after surgery.

"In many studies, researchers just consider nanoparticles as drug vehicles," added Daldrup-Link. "But they may have hidden intrinsic effects that we won't appreciate unless we look at the nanoparticles themselves."

The findings have been published in Nature Nanotechnology.