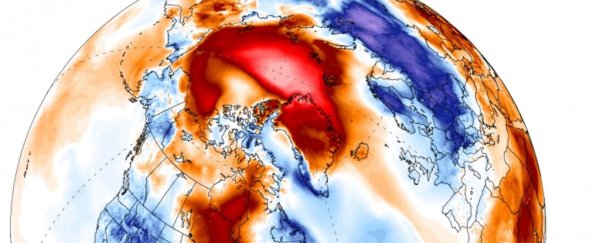

The sun won't rise at the North Pole until March 20, and it's normally close to the coldest time of year - but an extraordinary and possibly historic thaw swelled over the tip of the planet this weekend.

Analyses show that the temperature warmed to the melting point as an enormous storm pumped an intense pulse of heat through the Greenland Sea.

Temperatures may have soared as high as 35 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) at the pole, according to the US Global Forecast System model.

While there are no direct measurements of temperature there, Zack Labe, a climate scientist working on his PhD at the University of California at Irvine, confirmed that several independent analyses showed "it was very close to freezing," which is more than 50 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) above normal.

The warm intrusion penetrated right through the heart of the Central Arctic, Labe said.

The temperature averaged for the entire region north of 80 degrees latitude spiked to its highest level ever recorded in February. The average temperature was more than 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) above normal.

"No other warm intrusions were very close to this," Labe said in an interview, describing a data set maintained by the Danish Meteorological Institute that dates back to 1958. "I was taken by surprise how expansive this warm intrusion was."

The extreme event continues to unfold in the high #Arctic today in response to a surge of moisture and "warmth"

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) February 25, 2018

2018 is well exceeding previous years (thin lines) for the month of February. 2018 is the red line. Average temperature is in white (https://t.co/kO5ufUWrKq) pic.twitter.com/cLeMxSxvWo

Such extreme warm intrusions in the Arctic, once rare, are becoming more routine, research has shown. A study published last July found that since 1980, these events are becoming more frequent, longer-lasting and more intense.

"Previously this was not common," said lead author of the study Robert Graham, from the Norwegian Polar Institute, in an email.

"It happened in four years between 1980-2010, but has now occurred in four out of the last five winters."

Graham explained that these warming events are related to the decline of winter sea ice in the Arctic, noting that January's ice extent was the lowest on record. "

As the sea ice is melting and thinning, it is becoming more vulnerable to these winter storms," he explained.

"The thinner ice drifts more quickly and can break up into smaller pieces. The strong winds from the south can push the ice further north into the Central Arctic, exposing the open water and releasing heat to the atmosphere from the ocean."

Scientists were shocked in recent days to discover open water north of Greenland, an area normally covered by old, very thick ice.

"This has me more worried than the warm temps in the Arctic right now," tweeted Mike MacFerrin, an ice sheet specialist at the University of Colorado.

Such warm water is appearing to have an effect on air temperatures.

At the north tip of Greenland, about 400 miles to the south of the North Pole, the weather station Cape Morris Jesup has logged a record-crushing 61 hours above freezing so far this calendar year.

The previous record, dating to 1980, was 16 hours through the end of April in 2011, according to Robert Rohde, a physicist at Berkeley Earth, a nonprofit that conducts temperature analysis. At one point, the temperature was as high as 43 degrees Fahrenheit (6.1 degrees Celsius).

Kent Moore, a professor of atmospheric physics at the University of Toronto, who published a study in 2016 linking the loss of sea ice to these warm events in the Arctic, said a number of factors may have contributed to the latest warming episode.

For one, he said, recent storms have tracked more toward the North Pole through the Greenland Sea, drawing heat directly north from lower latitudes, rather than through a more circuitous route over the Barents Sea. He also said ocean temperatures in the Greenland Sea are warmer than normal.

"The warmth we're seeing in the Greenland Sea is definitely enhancing the warm events we're seeing," Moore said. "I'm surprised how warm it is, but I am not sure why."

The rise in Arctic temperatures is probably also tied to a sudden warming of the stratosphere, the atmospheric layer about 30,000 feet high - above where most weather happens - that occurred several weeks ago, Moore said.

Why these stratospheric warming events happen is poorly understood, as are their consequences. However, they tend to rearrange warm and cold air masses, and this latest one has also been linked not only to the Arctic warmth but also to the "Beast from the East" cold spell over Europe.

Moore stopped short of saying that the warm spikes observed in the Arctic in recent years are a sure sign that they are becoming a fixture of the winter Arctic climate; more data is needed, he cautioned.

Whether a blip or indicative of a new normal, scientists have uniformly expressed disbelief at the current Arctic temperatures and the state of the sea ice.

"This is a crazy winter," said Alek Petty, a climate scientist at NASA, in an interview. "I don't think we're sensationalizing it."

"It's never been this extreme," Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute, told Reuters.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.