Researchers in 2018 achieved a new kind of chimeric first, producing sheep-human hybrid embryos that could one day represent the future of organ donation – by using body parts grown inside unnatural, engineered animals.

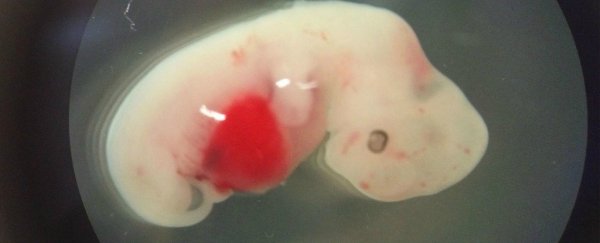

With that end goal in mind, scientists created the first interspecies sheep-human chimera in February, introducing human stem cells into sheep embryos, resulting in a hybrid creature that's more than 99 percent sheep – but also a tiny, little bit like you and me.

Admittedly, the human portion of the embryos created in the experiment – before they were destroyed after 28 days – is exceedingly small, but the fact they existed at all is what generates considerable controversy in this field of research.

"The contribution of human cells so far is very small. It's nothing like a pig with a human face or human brain," stem cell biologist Hiro Nakauchi from Stanford University told media at a presentation of the research back in February in Austin, Texas, explaining that, by cell count, only about one in 10,000 cells (or less) in the sheep embryos are human.

The research built on previous experiments by some of the same team that saw scientists successfully grow human cells inside early-stage pig embryos in the lab, creating pig-human hybrids that the researchers described as interspecies chimeras.

While the 'mad scientist' stereotype is fully present and accounted for in this kind of research, these divisive experiments could one day provide a unique solution for the thousands of people on donation waiting lists for live-saving organs – most of whom die before compatible body parts can be sourced for them, the researchers explain.

"Even today the best matched organs, except if they come from identical twins, don't last very long because with time the immune system continuously is attacking them," said one of the team, reproductive biologist Pablo Ross from the University of California, Davis.

Although it's still a long way off, organs produced in interspecies chimeras could be one way of producing enough supply to meet demand – by transplanting, say, a hybridised pancreas, from a sheep or pig, to a desperate patient.

For the transplant to work, the researchers think at least 1 percent of the embryo's cells would need to be human – meaning these first steps demonstrated in the sheep are still very preliminary.

But, of course, upping the human ratio in the chimera mix also inevitably increases ethical qualms about the kind of creature being created, ostensibly, for the sole purpose of having its essential organs harvested.

"I have the same concerns," Ross explained.

"Let's say that if our results indicate that the human cells all go to the brain of the animal, then we may never carry this forward."

There are no easy answers to the kinds of ethical questions this sort of research raises, but with someone being added to a US transplant waiting list every 10 minutes, the researchers say we shouldn't discount the possibilities of what chimeras could one day do for us.

"All of these approaches are controversial, and none of them are perfect, but they offer hope to people who are dying on a daily basis," Ross said.

"We need to explore all possible alternatives to provide organs to ailing people."

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in February 2018 in Austin, Texas.

An earlier version of this article was first published in February 2018.