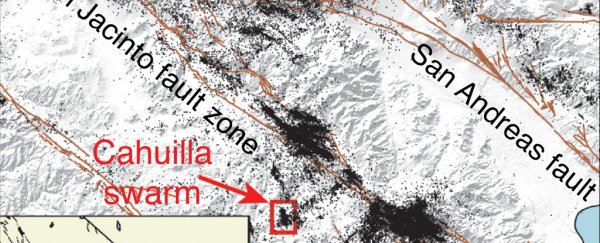

With the help of 3D modelling and machine learning, scientists think they've solved the mystery of the tiny earthquakes that regularly rumbled under Cahuilla, California from early 2016 to late 2019 – a period of almost four years.

Some sort of natural fluid, such as water or liquid carbon dioxide, is likely to be the culprit: as a new study lays out, it probably breached a barrier in the underground rock, changing the balance of pressure and friction along the fault zone, and leading to a long series of minor tremors.

The techniques deployed here could prove vital in understanding and predicting earthquakes in the future – both major quakes and smaller swarms, such as the one that happened near Cahuilla, and added up to tens of thousands of individual events.

"We used to think of faults more in terms of two dimensions: like giant cracks extending into the earth," says geophysicist Zachary Ross, from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

"What we're learning is that you really need to understand the fault in three dimensions to get a clear picture of why earthquake swarms occur."

Using neural networks - weighted AI models that mimic the human brain in how their nodes or 'neurons' interconnect - Ross and his colleagues processed more than 22,000 seismic events, ranging in magnitude from 0.7 to 4.4. The analysis revealed a complex, narrow fault line in 3D, stretching down about 8 kilometres (5 miles).

The model showed the probable presence of an underground reservoir, initially cut off from the fault zone before it leaked through and triggered the tremors. Spotting this was only made possible through the team's high-resolution modelling.

An illustration of how the fault line might look. (Ross et al., Science, 2020)

An illustration of how the fault line might look. (Ross et al., Science, 2020)

"The detail here is incredible," seismologist Elizabeth Vanacore from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, who wasn't involved in the research, told Maya Wei-Haas at National Geographic.

"This type of work is cutting edge and really where the science is going."

Swarms like the one studied here don't typically include any major quakes. They're also much less predictable than the big earthquakes, which usually start off with a significant shock that's then followed by slowly decreasing aftershocks.

What makes this particular swarm interesting is that it lasted so long – almost like a slow-motion swarm. Other swarms can last days, weeks or months. It's now winding down, the scientists say, possibly because the fluid has hit an impermeable barrier.

The next step is to test the modelling technique on other sites further afield, across southern California and elsewhere – it may be that natural fluid injections are responsible for more earthquake swarms, which seismologists can then test using this technique.

"These observations bring us closer to providing concrete explanations for how and why earthquake swarms start, grow, and terminate," says Ross.

The research has been published in Science.