Neuroscientists at Washington State University think they have figured out why cannabis is so notorious for causing the 'munchies' among users.

Their research on mice is the first to investigate how cannabis impacts the real-time activity of brain regions that control appetite.

The findings support an abundance of anecdotes and rigorous studies on humans, which all strongly suggest smoking, vaping, or eating cannabis can trigger acute cravings and have you headed for the pantry or fridge in no time.

Still, while recreational and prescription cannabis is commonly used to address appetite issues - like those that stem from eating disorders or chemotherapy – scientists know surprisingly little about the mechanisms behind this effect.

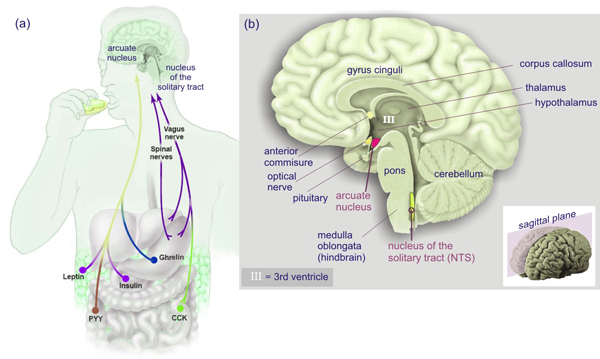

In recent years, numerous studies have pointed to the hypothalamus as an area of interest. This part of the brain sits deep within the organ and functions as a sort of 'control coordinating center' for the body, keeping hormones and the nervous system in balance.

At the bottom of the hypothalamus, just before it connects to the pea-sized gland responsible for producing hormones (including those associated with hunger), sits a clump of neurons called the arcuate nucleus, or the ARC.

This part of the hypothalamus is thought to regulate feeding behavior and metabolism.

Previously at WSU, researchers used rodents to show that cannabis exposure impacts genetic expression in the ARC.

Now, they have zoomed in even further and watched the firing activity of a small group of neurons in the ARC that have cannabinoid receptors.

Sure enough, when mice were exposed to vaporized cannabis, these neurons, called AgRP neurons, were disinhibited.

"When the mice are given cannabis, neurons come on that typically are not active," explains neuroscientist Jon Davis from WSU.

"There is something important happening in the hypothalamus after vapor cannabis."

Specifically, Davis and his colleagues found that cannabis exposure activated the cannabinoid type-1 receptors on AgRP neurons, and these receptors stopped the neurons from receiving 'stop' messages from other neurons.

Constantly in this 'go-mode', the AgRP neurons were linked to increased feeding among the lab mice.

When scientists inhibited this group of neurons, however, cannabis exposure no longer stimulated animal hunger.

"It is important to note here," the authors write, "that cannabis-induced feeding was not entirely ameliorated after AgRP inhibition, thus our studies do not rule out the contribution of separate CNS regions or additional signaling mechanisms… as important regulators of cannabis-induced feeding behavior."

Previous studies, for instance, have found that other neurons associated with appetite in the hypothalamus, called POMC neurons, are also impacted by cannabis and may play a role in the effect of munchies, too.

The study on AgRP neurons goes a step further and witnesses these changes in real time, using calcium imaging techniques. In addition, it links those changes to acute appetite promotion in living animal models.

The findings strongly suggest that this subset of neurons in the hypothalamus plays an important role in the 'munchies' – knowledge that could inform future drug research in the treatment of anorexia and weight loss.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.