A cycle featured in Maya calendars has been a mystery pretty much since it was rediscovered and its deciphering began in the 1940s.

Covering a period of 819 days, the cycle is referred to simply as the 819-day count. The problem is that researchers couldn't match that 819 days up to anything.

But anthropologists John Linden and Victoria Bricker from Tulane University now think they've finally cracked the code. All they had to do was broaden their thinking, studying how the calendar worked over a period of not 819 days, but 45 years, and relate it to the time taken for a celestial object to appear to return to approximately the same point in the sky – what's referred to as the synodic period.

"Although prior research has sought to show planetary connections for the 819-day count, its four-part, color-directional scheme is too short to fit well with the synodic periods of the visible planets," they write in their paper.

"By increasing the calendar length to 20 periods of 819-days a pattern emerges in which the synodic periods of all the visible planets commensurate with station points in the larger 819-day calendar."

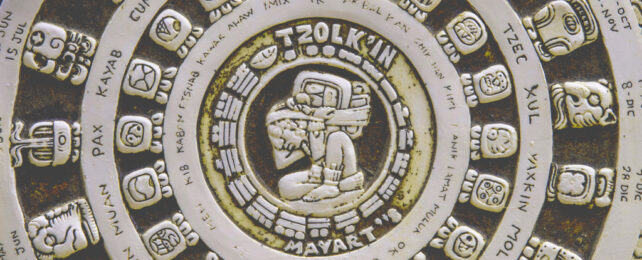

The Maya calendar is actually a complicated system made up of smaller calendars, developed centuries ago in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Of the component calendars, the 819-day count is the most baffling to modern anthropologists.

It's a glyph-based calendar that is repeated four times, with each 819-day block corresponding with one of four colors and, scientists initially thought, a cardinal direction. Red was associated with east, white with north, black with west, and yellow with south. It wasn't until the 1980s that researchers realized that this assumption was incorrect.

Instead, white and yellow were associated with zenith and nadir respectively – an interpretation that fits with astronomy, as the Sun rises in the east, travels across the sky to its highest point (zenith), sets in the west, then travels through its nadir to rise again in the east.

There were other clues to suggest that the 819-day count was associated with the synodic periods of visible planets in the Solar System. The Maya had extremely accurate measurements of the synodic periods of the visible planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

However, the difficulty lay in trying to figure out how these synodic periods worked in the context of the 819-day count. Mercury is easy; it has a synodic period of 117 days, which fits into 819 days exactly seven times. But where did the rest of the planets fit?

It turns out that each of the visible planets has a synodic period that exactly matches a number of cycles of the 819-day count. Venus' synodic period is 585 days; that matches neatly with 7 counts of 819-days. Mars has a 780-day synodic period; that's exactly 20 counts of 819-days.

Jupiter and Saturn aren't left out, either. Jupiter's 399-day synodic period fits exactly 39 times into 19 counts; and Saturn's 378-day synodic period is a perfect match for 6 counts.

And there's even a compelling link with the 260-day calendar known as the Tzolkʼin. Twenty 819-day periods is a total of 16,380 days. If you multiply the Tzolk'in 63 times, you get 16,380 days. In fact, 16,380 is the smallest multiple that 260 and 819 have in common. So the two link up beautifully with the 20-cycle 819-day count laid out by Linden and Bricker.

"An expansion of the standard 4 × 819-day cycle to 20 periods of 819 days does provide a larger calendar system with commensurations at its stations for the synodic periods of all the visible planets. Most importantly this larger calendar system of 20 periods of 819 days provides a mechanism for reestablishing the day number and day name of the Tzolk'in each time the cycle of 20 periods of 819 days begins," the researchers write.

"Rather than limit their focus to any one planet, the Maya astronomers who created the 819-day count envisioned it as a larger calendar system that could be used for predictions of all the visible planet's synodic periods, as well as commensuration points with their cycles in the Tzolk'in and Calendar Round."

Any time historians are required to interpret significant measurements of ancient origins, they run the risk of reading too deeply and misattributing values. That's not to say Linden and Bricker's proposal is numerology dressed up as academia, though it is important to let science do its work and keep an eye out for critiques and rebuttals.

Still, the Maya calendar is far from a simple system based on basic astronomy. We shouldn't be at all surprised that the Maya's measure of the cosmos embraced such a great expanse of space and time.

The research has been published in Ancient Mesoamerica.