Scientists have managed to grow tiny human stomachs from stem cells, and they're using them to study gastric diseases such as stomach cancer and ulcers, and hope to one day use them to grow stomach tissues for transplanting.

If you ever visit a doctor about some kind of persistent stomach problem, such as frequent bloating, cramps, or constipation, you'll quickly discover just how mysterious the human stomach is, even to the experts. As you're referred to an ultrasound machine, a nutritionist, and quite possibly another doctor, and asked to trial various diet changes and treatments over the course of several months, you'll probably be wondering why there isn't a better way. Maybe you have the very common gastrointestinal disorder, irritable bowel syndrome. It's said to affect up to 20 percent of the global population, but we still have no idea what causes it, or really how to treat it.

Around half the world's population is affected by a gastric disease caused by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which penetrates the lining of its host's stomach and can cause an array of symptoms including nausea, bloating, vomiting, and can even lead to ulcers and stomach cancer. And yet, the link between H. pylori and different types of stomach cancers remains frustratingly complex, with research suggesting that an H. pylori infection might decrease the risk of some cancers but increase the risk of other cancers.

So what if there was a way for scientists to mess around with as many stomachs as they wanted, endlessly, until they had this hollow, muscular enigma pegged?

Looks like there just might be.

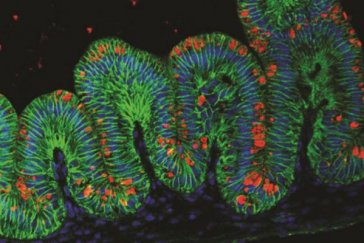

A team led by James Wells, director of the Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Centre in the US, has developed tiny, pea-sized human stomach replicas, by growing them from stem cells in petri dishes. They're so perfectly formed, that the lining inside these hollow, oval-shaped 'gastric organoids' is folded neatly into a complex arrangement of glands and pits, just like a real stomach.

Which means they look great, but do they work? According to Stuart Clark at The Guardian, the team has found that its miniature stomachs respond to various infections in a similar way to how actual stomachs respond to them, which gives them the perfect testing ground for diagnosis and treatments.

"There hasn't been any good way to study human stomach disease before because animals just don't get the same diseases," Wells told Clark.

Once the team managed to perfect their mini-stomachs, they started infecting them with H. pylori to see how the stomachs would react. This mysterious but prevalent bacterium has been extremely difficult to study because it doesn't seem to affect lab animals adversely at all. But when the bacteria were injected into the mini-stomachs, they acted just like they would in a real human stomach, so the scientists now have a perfect window into their invasion strategies.

First, says Clark, the bacteria started to inject proteins into the cells around them, and these started to multiply. "This is the hallmark of infection," said Wells. "We can now very effectively study the bacteria and how it generates diseases. This has never been possible before with human tissue in vitro."

Now that the team has their mini-stomachs working to sort out the mysteries of gastric diseases, the next step will be using this technology to grow tissue to be grafted onto actual human stomachs, where cancers or ulcers have left holes in the lining. The team is actively testing out their tissue-replacment technique now on mice.

The team has published the research today in the journal Nature.

Source: The Guardian