Scientists have 'puppeteered' the movements of a jellyfish and made it even faster than the real thing.

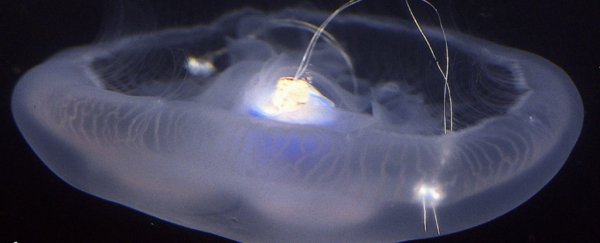

Taking artificial control with a microelectronic implant, researchers have increased the natural swimming speed of a live moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) by nearly threefold.

What's more, they achieved this with only a little bit of external power and twice the amount of metabolic effort from the animal.

"Thus," the authors conclude, "this biohybrid robot uses 10 to 1,000 times less external power per mass than other aquatic robots reported in literature."

Jellyfish are known to be incredibly efficient swimmers, much more so than any machine we humans have created, so their low cost of transport makes them an ideal "natural scaffold".

While it's true certain underwater vehicles can travel much faster than a jellyfish, so far, robots that try and mimic jellyfish behaviour require orders of magnitude more energy and are usually tethered to an external power supply.

The real things, on the other hand, are slow and steady, unencumbered explorers, capable of self-healing. If we can properly control them, some think they could be an intriguing new way to expand ocean monitoring.

"Because jellyfish are naturally found in a wide range of salinities, temperatures, oxygen concentrations, and depths (including 3,700 m [12,100 feet] or deeper in the Mariana Trench)," the authors of the new study propose, "these biohybrid robots also have the potential to be deployed throughout the world's oceans."

Of course, that would require a lot more control than we currently have. So far, the team has merely shown they can enhance jellyfish swimming without undue cost to the metabolism or health of the animal.

The key to this small but significant step is a portable microelectronic swim controller, which, when attached to the jellyfish, can generate pulse waves and stimulate muscle contractions.

Through this technology, scientists can speed up a jellyfish's propulsion until it hits an optimal point, where the greatest speed is achieved with the smallest energy output.

By hijacking the metabolism and muscles of the jellyfish in this way, researchers got the creature moving 2.8 times faster than its natural swimming speed.

The team hopes their work can lead to newer underwater vehicles that can some day explore for longer periods of time, while also making minimal disturbances wherever they may roam.

With some more tweaking, there's a chance we might even be able to use real jellyfish to study distant corners of the ocean, similar to the way we currently use tagged mammals.

"Moreover, because jellyfish do not have a swim bladder, they can reach 3,700-metre [12,100-foot] depths in the ocean," the authors write.

"Only the microelectronics will require hardening for operation at high pressures."

Who knows, perhaps it will be an army of biohybrids that one day reveal the vast untold mysteries of our oceans.

The study was published in Science Advances.