There are lots of animals that need conservation help. Cuddly creatures like pandas and koalas, or brainy beasts like whales and octopuses, just to name a few. But a team of scientists is urging us to not forget one particularly unlovable group that also needs our assistance: parasites.

Parasites, the team explains, have a bit of a PR problem. They're not just blood-sucking monsters, or freeloading fiends (which, don't get us wrong, they still are). As the team says, parasites also perform incredibly significant ecological roles.

Parasites influence the survival and reproduction of many host species, and form vital links across food chains. For example, they increase predatory birds' killifish kills by up to 30 times by messing with the fish's brains in a way that makes them more vulnerable to the birds. Alas, so many of these complicated interactions are unknown to us.

"Parasites are an incredibly diverse group of species, but as a society, we do not recognise this biological diversity as valuable," says ecologist Chelsea Wood from the University of Washington.

"The point of this paper is to emphasise that we are losing parasites and the functions they serve without even recognising it."

The paper is part of an entire issue of the journal Biological Conservation devoted to parasite conservation. There's an article about how efforts to save parasitic host species still threaten the parasites due to differences in captivity, and one on how we assess the conservation status of parasites. The focus of Wood's team's paper is on how to create a global parasite conservation plan.

"Found throughout the tree of life and in every ecosystem, parasites are some of the most diverse, ecologically important animals on Earth - but in almost all cases, the least protected by wildlife or ecosystem conservation efforts," the authors explain in their paper.

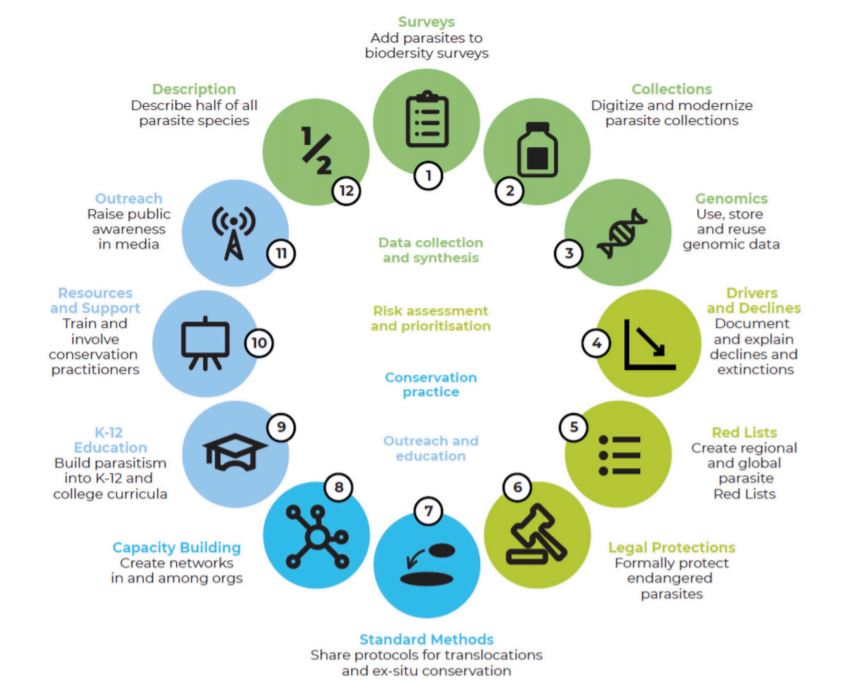

"Our working group identified 12 goals for the next decade that could advance parasite biodiversity conservation through an ambitious mix of research, advocacy, and management."

Now, it might sound a bit weird to get so invested in parasites, when we're not even sure how all the animals they live in are faring, and at a time when all sorts of species are facing extinction threats.

As the team explains, cuddly or charismatic animals get the bulk of funding when it comes to conservation, and we've only identified around 10 percent of the parasites that inhabit them. That's a problem.

"If species don't have a name, we can't save them," says co-lead author Colin Carlson, a biologist at Georgetown University.

"We've accepted that for decades about most animals and plants, but scientists have only discovered a fraction of a percentage of all the parasites on the planet. Those are the last frontiers: the deep sea, deep space, and the world that's living inside every species on Earth."

The team of researchers from the US, Spain, and Australia have identified 12 goals for the next decade to help keep our parasitic friends around for generations to come.

These are split into four groups – data collection and synthesis, risk assessment and prioritisation, conservation practice, and outreach and education.

As you can see in the image above, these goals are ambitious. Everything from education about parasitism to formally protecting endangered parasites needs to get done.

The twelfth goal though, might be the most pioneering of them all.

"In the spirit of that challenge, we propose a final ambitious goal: describe half of parasite diversity on Earth," the team writes.

"Some targets will be difficult to estimate, and initial estimates will have wide confidence intervals, especially for groups like parasites of invertebrate hosts that are under described and under-represented in biodiversity data. Even so, systematically using the best-available methods to define initial 50 percent description targets will vastly improve our understanding of global parasite biodiversity."

Just a note here that the team isn't focused on human or domesticated animal parasites – so you don't need to worry about them formally protecting the ring worm, ticks, or lice we all know and love (or hate).

But that doesn't mean that the researchers don't expect some backlash, especially from those not already in the parasite biology corner.

"Fully describing 50 percent of parasite biodiversity, like all the other goals identified here, could be dismissed as overly ambitious and too low priority given the many fronts on which resources for combatting global change biology are already spread thin," the team writes.

" Climate change, emerging diseases, and mass extinction are already monumental crises that desperately need more personnel and funding.

"However, we believe all available scientific evidence suggests that neglecting the hidden world of parasites only limits our efficacy in fighting these other battles, and will lead to more and worse unexpected outcomes."

So next time you think of animals that need protecting, maybe spare a thought for the humble parasite. Or we might end up losing these creatures and any vital role they play within our ecosystems before we even discover what they are.

The paper has been published in Biological Conservation.