During a hot summer night in the Australian state of New South Wales, ecologist Heloise Gibb and her team were hunting for scorpions in some arid scrubland.

Using special UV-proof glasses and UV flashlights, they were looking for a flicker of fluorescence indicating a scorpion, which have become abundant in the damaged, sandy deserts of Australia.

"Scorpions fluoresce in the light of our UV [flashlights] – so all you can see is scorpions," she explains.

"We used tongs to pick them up by their tails for measurements, because these scorpions are big and nobody wants to be stung."

Although this exercise sounds like it could be in an episode of a strange reality TV show, there's a good reason to be measuring scorpions – the protection of biodiversity.

Australian native scorpion species can grow up to 12 centimetres (4.7 in) long. Many of them thrive in the arid regions of Australia; in fact, Gibbs found up to 600 scorpion burrows per hectare, pockmarking the landscape.

But we don't know if scorpions were always so abundant, or if drastic damage to the landscape by European colonisers - especially with introduced animals and the eradication of native species - has accidentally helped the scorpions to thrive.

Hence, Gibbs asks, "were they always so abundant or might this plethora of scorpions be the result of wiping out other species from the ecosystem?"

Thanks to five years of experiments by the team from La Trobe University, the University of New South Wales, and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, we now know that the lack of native mammals – particularly digging species such as bilbies (Macrotis lagotis), has helped scorpion populations to run wild, and that's not necessarily a good thing.

"Island biota are vulnerable to extinction caused by introduced predators and competitors, due to their long evolutionary history of isolation," the team writes in their study.

"Since European colonisation 230 years ago, the island continent of Australia has experienced the highest contemporary rate of mammal loss globally (29 species extinct; 21 percent threatened)."

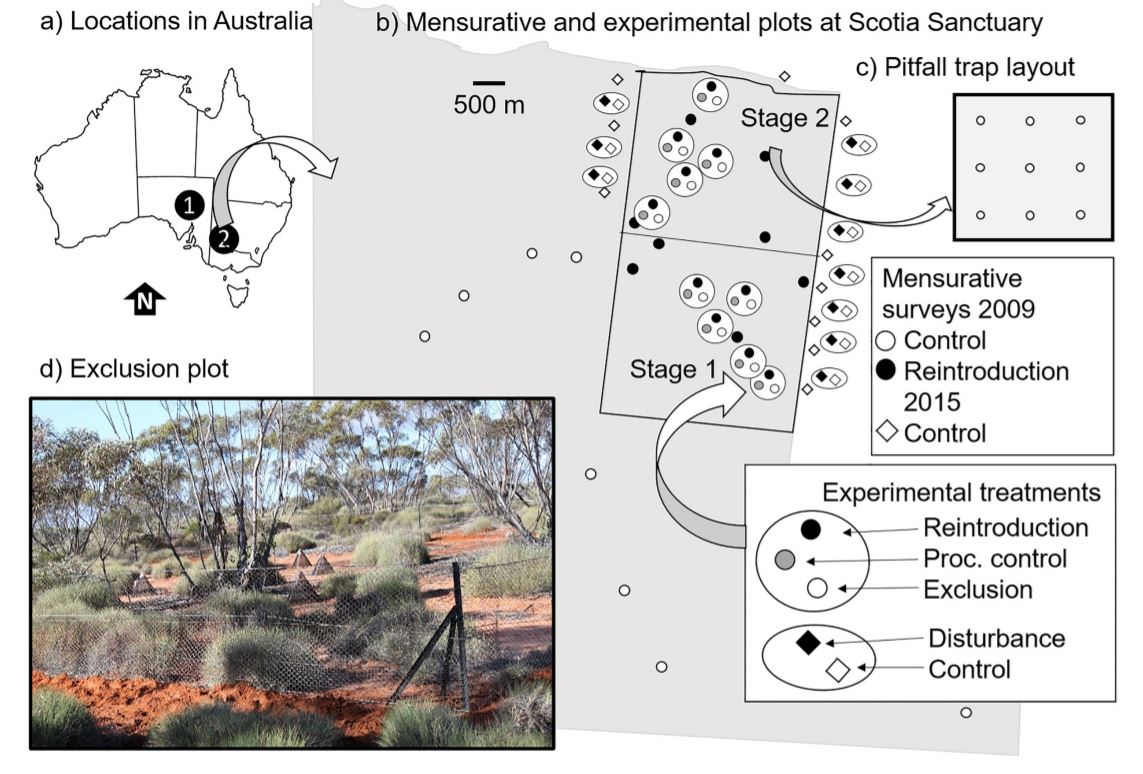

The researchers went to two predator protected wildlife sanctuaries – Arid Recovery in northern South Australia, and Scotia Wildlife Sanctuary in south-western New South Wales.

These predator-protected sanctuaries allow native mammals to return and flourish in an area, and are an incredibly important part of Australia's habitat restoration programs.

Within these sanctuaries, the researchers set up areas where the native mammals could travel through, as well as small fenced areas where the animals wouldn't be able to get into.

The team found that in the areas where digging animals could roam, there was more plant cover, and fewer scorpion nests. The team also notes that the mammals - such as bilbies and bettongs - were eating the scorpions, which also significantly lowered the numbers.

But they also found that a decrease in scorpion population was also achieved in areas where the researchers mimicked the digging activities of native mammals.

"Even without the impacts of predation, increasing densities of digging mammals will lead to declines in scorpions," they write, speculating that this may be due to increasing their levels of fear, or reducing scorpion's ability to find food due to changes in the landscape.

Interestingly though, scorpions weren't the only ones affected by this return of the mammals. Spiders also seemed to thrive when mammals weren't there, with spider composition changing and overall amounts of spiders increasing when the native diggers were kept out.

That said, losing too many could also be problematic, as spiders play a key role in regulating insect populations. The researchers point out we don't know what the abundance levels of these digging mammals were before Europeans disturbed these ecosystems.

"Reintroducing locally extinct digging mammals provides an opportunity to restore ecosystems, but it's hard to get right because we don't know what Australia's ecosystems were like 200 years ago," Gibb explains.

"It's important to consider that reintroductions may also result in unexpected consequences for ecosystem structure. Over-predation on one species might lead to increases in others and these changes can cascade all the way through from predators to plants."

These findings add to a growing body of evidence on just how interconnected our ecosystems are, where a change in the presence of one type of animal can have such profound effects across seemingly unrelated species. Amidst a mass global extinction of our own making, understanding these connections is more vital than ever.

The research has been published in Ecology.