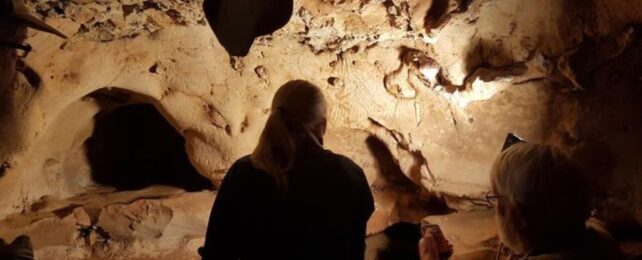

A gallery of ancient cave markings determined to have been created as far back as 75,000 years ago is likely to be the handiwork of Neanderthals.

The team of researchers behind an analysis of artwork found in the French cave of La Roche-Cotard argue this is the earliest unambiguous example of Neanderthal cave engravings ever discovered, demonstrating our closest cousins shared our creativity and desire for self-expression.

When dating the sediment that used to cover the cave's entrance, archaeologist Jean-Claude Marquet of the University of Tours, France, and his colleagues found that the artwork had to have been sealed off from the outside world sometime between 51,000 and 57,000 years ago.

Only when the entrance was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century were the chambers opened once again and their long-held secrets revealed.

The findings suggest that Homo sapiens could not have entered the cave and made the engravings after our ancestors finally arrived in western Europe, around 45,000 years ago.

"Fifteen years after the resumption of excavations at the La Roche-Cotard site, the engravings have been dated to over 57,000 years ago and, thanks to stratigraphy, probably to around 75,000 years ago, making this the oldest decorated cave in France, if not Europe!" Marquet and colleagues argue.

At this point, it's worth noting that recent evidence uncovered in Lebanon suggests Homo sapiens left Africa and traveled to western Europe earlier than experts once thought. Though they may have come within striking distance of the cave, these initial excursions seemed to have largely skipped what is now France, possibly because of resistance from Neanderthals already occupying the region.

Artifacts found at and adjacent to the La Roche-Cotard cave suggest Neanderthals lived on the banks of the River Loire from just under 100,000 years ago to 65,000 years ago.

The finger drawings they made on some of the cave's walls sometime during that 35,000-year-long stretch do not depict obvious figures, like animals or plants. But to be fair, no known hominin, not even our own species, was creating figurative art at this time.

The oldest known figures painted by Homo sapiens, or any species for that matter, were found on an island in Indonesia and date to about 45,000 years ago.

By comparison, the beginning of abstract, expressionist art, like those made with parallel lines or circles, is harder to determine. It hinges on what experts consider 'art' to actually be.

Next to some random scratches that seem to have been made by animals, researchers working on the La Roche-Cotard cave have cataloged dozens of "elongated or dotted, spatially organized marks" that look as though they were made by hominins.

Marks found on walls attributed to animal claws are thinner, deeper and V-shaped, contrasting with shallower and U-shaped marks, "consistent with the morphology of a fingertip or similarly shaped tool."

By rubbing the light, porous rock, whoever was using this cave thousands of years ago probably molded the softer exterior film, Marquet and his team explain, creating a "smooth and regular groove".

Since then, weathering of the cave's walls has left few clean boundaries, but these markings were probably once clear to see.

One section of the cave art centers around a buried bivalve shell. The finger engravings made here almost seem to "underline its presence", the researchers write.

The circular pattern, below, was made with strikingly deep and apparently forceful finger traces, the edges of which appear to have eroded over time.

Another triangular collection of markings, by comparison, shows an abrupt and purposeful boundary for where the parallel finger markings start and end.

Another particularly striking 'panel' is composed of a smattering of finger dots.

Analyzing the characteristics of the whole collection Marquet and colleagues suggest these designs are more "more graphic than functional", representing an "organized, deliberate composition" driven by "conscious design and intent".

Whether they symbolize some greater meaning is impossible to say. But growing evidence suggests Neanderthals might have been far more artistic than we once gave them credit for.

A highly contentious object found outside the cave dated to about 75,000 years ago, for instance, called the Mask of la Roche-Cotard, looks suspiciously like a face, with eyes that seem to have been carefully carved into a slab of flat flint. On the other hand, given our propensity for identifying faces in patterns where none exist, it could be a misinterpretation.

What's more, in 2021, a bone carving found in Germany, which was probably carved by Neanderthals, was dated to around 51,000 years old. It might have even been boiled to make it softer to work with.

In Spain, meanwhile, red-painted cave walls and hand stencils date back more than 60,000 years, and some scientists have used that timeline to argue that they were made by Neanderthals.

Of course, there's always a chance that Homo sapiens arrived in western Europe earlier than archaeological evidence suggests, but given the facts that experts have on hand, it's getting harder to argue that Neanderthals weren't artists of at least some caliber.

There's even evidence they were mixing red ochre paint as far back as 250,000 years ago.

Archaeologist Dirk Leder, who helped uncover the bone carving in Germany, has a proposal even more controversial. In 2021 he told Amy McDermott at PNAS that it's possible Neanderthals may not be the earliest hominins capable of expressing themselves through abstract art.

Some evidence indicates Homo erectus was engraving shells with abstract patterns as far back as 500,000 years ago in Java, Indonesia.

Whether that represents a form of legitimate artwork remains highly contentious, but in archaeology as in art, it's wise to keep an open mind.

The study was published in PLOS ONE.